Protecting Endangered Species: Conducting Mussel Surveys

Diver collecting freshwater mussels in the Apalachicola River Basin, FL. (Credit: Greg Zimmerman / EnviroScience, Inc.)

Diver collecting freshwater mussels in the Apalachicola River Basin, FL. (Credit: Greg Zimmerman / EnviroScience, Inc.)*This is part two of a two-part story on endangered mussels. To read part one, click here*

With over 300 endangered mussel species in the United States, environmental agencies like EnviroScience rise to the challenge of protecting these vital species. When new construction sites are determined, the Endangered Species Act steps in to protect any endangered wildlife within the impacted area. Unfortunately, the protocols surrounding these protections can be complex and difficult to understand, making the work of scientists like Greg Zimmerman, Corporate Vice President for EnviroScience and an endangered mussel surveyor, vital to protecting biodiversity.

Why are Endangered Mussel Surveys Conducted?

Depending on the state, they may have their own list of protected mussels or rely on the list of federally protected mussels to guide their environmental policies, and it’s often a combination of both. For example, Ohio protects all native freshwater mussels, whereas other states only regulate federally and state-listed mussels, but not all species. Regardless of the referenced list, each state has an agency or multiple agencies tasked with managing environmental reviews that impact mussels.

Endangered mussel surveys are a necessary step in project planning because the distribution of mussels and species assemblage relative to a planned project is critical to completing the required environmental documentation.

In Ohio, the ODNR and USFWS are typically responsible for reviewing project plans and environmental reviews to ensure that protected species are considered. These agencies have classified all of Ohio’s major waterways into areas known to have mussels and the potential for federally listed species within these reaches.

A Group 1 stream means a small to medium stream where mussels may be present, but it’s not known to have federally listed species. A Group 2 stream is a small to medium stream where federally listed species are known to exist. Little Darby Creek is both a Group 1 and Group 2 stream, depending on the location.

Similarly, a Group 3 stream is a large river where mussels are present but no known federally listed species, and a Group 4 stream is a large river where endangered mussels may be present, like some sections of the Ohio River and the Muskingum River.

Having clear guidelines and boundaries makes urban planning easier. EnviroScience works closely with its clients and the respective state agencies. “That’s the kind of work that we do. We work as an intermediary between the project owner and the agency in finding the most efficient way to get everything done,” says Zimmerman.

Mussels are endemic to specific areas, and project impacts can disturb or kill the native population. Unlike fish that can move away from construction areas, mussels don’t move. Often when the project cannot be moved, a mussel salvage (relocation) may occur to preserve the population. Divers and biologists enter the water and move the mussels away from the area of direct impact, but it can be a very labor-intensive process.

“Often you move them out of the way before the project because they live a long time—they don’t repopulate immediately, similar to an old-growth forest, it’s not something that’s going to come back immediately,” Zimmerman emphasizes. Because the population cannot quickly repopulate, surveys and relocations help prevent species and ecological function loss.

Mussel Survey crew on on the Muskingum River, Ohio (Credit: EnviroScience, Inc.)

Conducting Endangered Mussel Surveys

The procedures for conducting a mussel survey vary widely from state to state, and most states also have strict and specific guidance on who can perform mussel surveys, as they are very difficult to identify, and a relatively high level of experience is needed to perform and report the fieldwork to meet agency expectations.

Previously, mussel survey methods were proposed project-by-project, but this is no longer the case. Most states have basic survey protocols, which may need to be modified based on the project type and site conditions. Knowing when modifications may make sense rather than following the survey “recipe” is another reason most project owners know to utilize experienced surveyors and salvagers like EnviroScience.

Mussel surveys and relocations typically begin with defining the Area of Direct Impact (ADI). The ADI is typically where mussels are usually relatively certain to be killed or severely impacted by construction, scour, water quality, temperature, etc. Then survey limits are defined around the ADI in terms of how far upstream, laterally, and downstream a survey should occur.

In some states, a “Recon” survey may be performed ahead of time at the site to determine if mussels and mussel habitats exist before conducting a formal survey.

After establishing the survey boundaries, the team of surveyors, often through a combination of methods including hand searches by wading, snorkeling and diving, are deployed to meticulously search for mussels.

Search Methods and Finding Endangered Mussels

Specific search methods include time searches in cells (sections of the survey limits divided into squares like a checkerboard), transect searches (essentially underwater measuring tapes), quadrats, and moving transects. If endangered mussels are detected, the mussels collected in the field are put back where they were found.

Additionally, if endangered mussels are found, a project typically cannot move forward without informal coordination with federal and state agencies to avoid project impacts. If impacts can’t be avoided, the development of a Biological Assessment (BA) is typically required to be submitted to USFWS for review.

The Biological Assessment is then approved via a Biological Opinion (BO) which can allow some impacts to endangered species so long as their existence is not in jeopardy. The BO will also call for certain conservation measures, such as construction site best management practices like monitoring water quality and relocating mussels out of the ADI before construction.

“The worst case for a project owner is when we detect an endangered mussel during a relocation project in an area where endangered mussels were not expected. Then you have a situation where a project is likely about to go to construction, contractors can charge the owner fees for delays, and the project can’t happen until we get environmental clearance and things turn into an emergency. These events can happen and I think EnviroScience has the best record out there for working through these issues,” says Zimmerman

Zimmerman notes this is why doing a survey correctly up front, anticipating impacts and pushing for a mussel relocation scheduled as far ahead as practical in areas of uncertainty in terms of endangered species is important.

In cases where no endangered mussels are detected, or none are expected like in certain stream classifications, mussel surveys can sometimes move directly from survey mode to relocation mode where only non-listed mussels are relocated, or in some cases, no relocation may be required at all depending on the state/location.

(Credit: Greg Zimmerman / EnviroScience, Inc.)

Equipment Used for Endangered Mussel Surveys

“We often use transects, which are weighted lines that we’ll stretch across the river bottom and are marked out, so we know where the mussels were collected and where the divers are,” says Zimmerman.

Transects can also be used to create a cell grid on the stream bottom, like a checkerboard, with each square receiving a specific level of search time (effort). The weighted line allows the divers to be more easily tracked in the water.

EnviroScience also uses specialized boats and diving equipment. The standard method of diving in rivers uses surface-supplied air hardhat diving, including video and communications for safety and efficiency. Because of its life support equipment, a very high level of training and equipment protocols and maintenance is required.

Zimmerman, who received a degree in Environmental Biology from Hiram with a heavy concentration in art, initially used his skills to create maps of the project area and the location of the mussels living there relative to the impacts. His diverse experience and educational background in biology and art have helped EnviroScience and its services stand out.

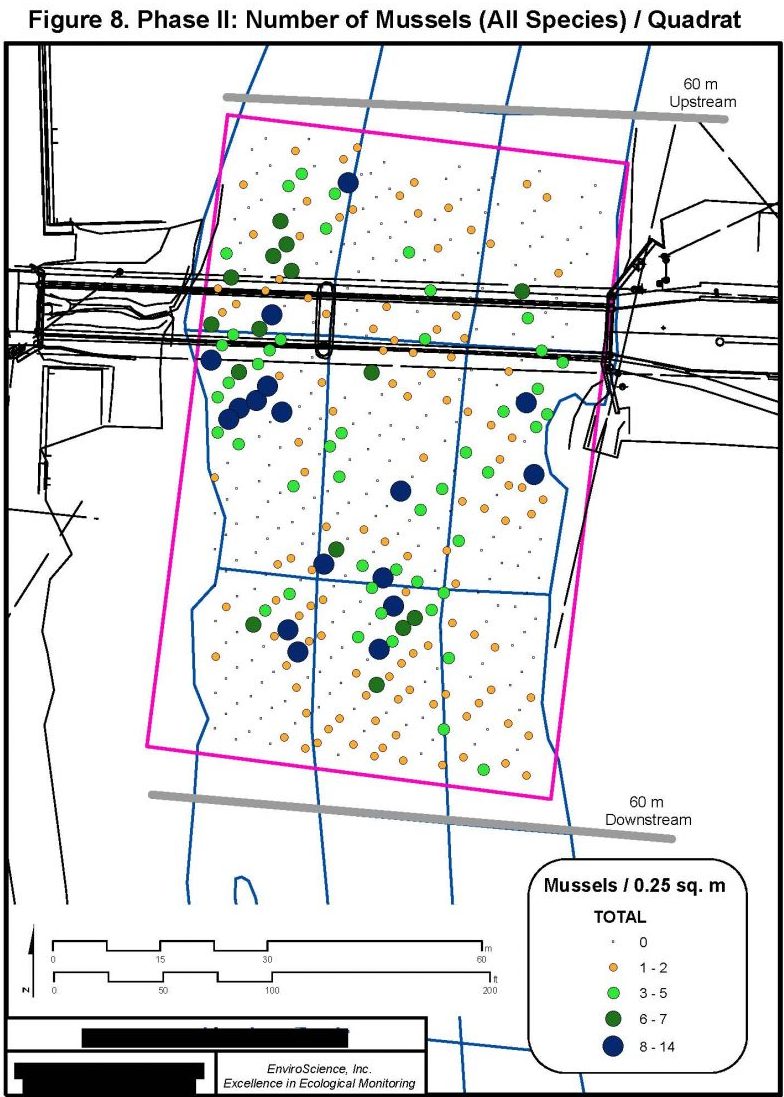

“One of the things that I think led to our success was being able to graphically display data in relation to a project in a way that is easier to understand,” he adds. “Creating maps in GIS was my art outlet, I loved taking our field data and the engineering information and combining these things to create that ’a picture says 1,000 words.’ Now we have an entire GIS/CAD department and they’ve done an amazing job to streamline the process, but I see the foundation of my original maps in our work products which is fun.”

In particular, mussel relocations completed under a BO are very technical. “You work through the substrate like underwater archaeology—you work your way through one way, pull the mussels out and repeat over the same area continuing the process until you reach an established threshold where the agencies can be confident most of the mussels are cleared,” Zimmerman outlines. Easier said than done, Zimmerman adds, “A lot of times in freshwater, you can’t see, so you have to go by feel—it’s a very resource-intensive process.”

“The simplest equipment we use is a quadrat, which is just a square usually made out of rebar or PVC and a scoop,” explains Zimmerman. For detailed mussel population studies, often required for endangered mussels, the quadrats are disbursed throughout the area in a grid pattern with sometimes 100s of samples, and divers systematically search each box for mussels. The number of quadrat samples required is often based on statistical models developed by the USGS.

A diver salvaging freshwater mussels for relocation. (Credit: EnviroScience, Inc.)

Monitoring after Construction

During and after projects that impact endangered mussels, monitoring the species often continues. EnviroScience uses turbidity sensors to track water quality before, during and after construction for things like turbidity and pH from concrete work and Passive Integrated Transponders (PIT tags) by BioMark/Merek to track mussels that were relocated.

One of EnviroScience’s biggest projects that continues to require monitoring is the PennDOT Hunter Station Bridge. “For the Hunter Station Bridge we used EXO2s upstream, nearfield and far field from the bridge site during construction to monitor and ensure that when they’re doing concrete pours or there is runoff from rain events, we can track how it relates to mussels,” Zimmerman adds.

The Hunter Station Bridge in Pennsylvania was the largest relocation of endangered mussels ever completed in the U.S. According to Zimmerman, the bridge has a very large population of endangered mussels in the area, including directly underneath. Due to the population size and the potential impacts, the project took over 10 years to plan and complete. Over 190,000 mussels were moved to different streams and rivers in various states over 2 years, earning PennDOT District 1-0 the Pennsylvania Governor’s Award.

“Usually, you just move them upstream to a suitable habitat near the bridge; it’s pretty rare where you move mussels to different locations even within the same river, let alone 6 states and the Seneca Nation of Indians,” Zimmerman says. However, “The Hunter Station project was so big that it could have actually jeopardized the existence of the two species that would have been impacted without these conservation measures.”

Though unconventional, relocation was necessary considering the potential species loss and the large number of mussels present in the area. “It was a really big deal because there were so many mussels there, but there was nowhere else to put the bridge—it had to be fixed,” explains Zimmerman. “Locals were looking at a 50-mile detour, and it was a critical route for emergency services. The design and construction teams were able to keep the bridge open through most of the replacement, which was another huge win considering the endangered mussel resources nearby.”

Completing the project took years, but the time was well-spent. Zimmerman expands to say, “We have the rainforest of mollusk diversity in the world.” Losing even two species of mussels could lead to further ecosystem instability as native freshwater mussels naturally improve their ecosystem.

Pingback: FishSens Magazine | Sacramento Chinook Salmon: Positive Population Trends - FishSens Magazine

Pingback: Environmental Monitor | Protecting Endangered Species: Why Freshwater Mussels Matter - News

Pingback: FishSens Magazine | Impacts of Thermal Stress on Aquatic Species - FishSens Magazine