Near threatened Puerto Rico corals, contaminant levels among highest ever recorded by NOAA program

A diver conducts a sampling transect (Credit: NOAA)

The Río Loco once tumbled from Puerto Rico’s central mountain range and snaked its way through dense forest before pouring into Guánica Bay in the island’s southwest corner.

The forest over time became checkered with sugarcane and coffee plantations. In response to shifting government policies in the 1950s, much of the watershed’s farmland gave way to urban development and industrialization. A vast freshwater lagoon was drained, reservoirs were built and long stretches of the river were forced into arrow-straight channels.

Scientists knew the land-use transformation had environmental consequences for Guánica Bay, and particularly for the coral reefs that lie just outside it.

Still, they were surprised by results from a three-year National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration study: Sediments in Guánica Bay contained some of the highest levels of PCBs, chlordane, chromium and nickel ever measured in the nearly three-decade history of NOAA’s National Status and Trends monitoring program.

Except for chromium, those pollutants and others also were present at lower—but still potentially toxic—levels in coral samples taken just outside the bay.

“That we’re finding PCBs and other chemicals in Guánica Bay is not surprising,” said David Whitall, a NOAA senior scientist who co-authored the report. “But the levels we’re finding are very surprising. For nickel, of the top 20 values we’ve ever measured, 15 of them are from this study in Guánica Bay.”

PCBs—industrial solvents found in dyes, hydraulic fluids and numerous other applications—and chlordane, a pesticide, have been banned for decades but linger in the environment. Both have been linked to a range of serious health issues in animals and humans, and are considered probable carcinogens by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Nickel and chromium are naturally occurring elements, but mining and industry can release high concentrations of them into the environment. Exposure to some forms of the metals is known to cause cancer.

Several other contaminants—including DDT, arsenic and mercury—also were found in sediment at potentially toxic levels.

Guanica Bay, on the southwest corner of Puerto Rico, from the air (Credit: NOAA)

While further research is needed to draw a clear link to the chemicals, the team found that corals covered less of the seafloor immediately offshore from Guánica Bay than in an adjacent study area called La Parguera or elsewhere in the region.

“We’re pretty confident these are toxic levels to the organisms that live in the sediments,” Whitall said.

The researchers tested dozens of chemical contaminants using one-time sampling of sediment and coral tissue at random sites. They collected sediment from a research vessel using a Ponar sampler, while SCUBA divers gathered coral samples using a hammer and a titanium punch.

A third of coral reefs in the Caribbean are threatened by runoff of land-based sediments, nutrients and pollutants, according to the NOAA study. The interagency Coral Reef Task Force, of which NOAA is a lead agency, named Guánica Bay one of three priority watersheds in U.S. coastal waters designated for restoration.

The effort to restore the Guánica Bay ecosystem is multifaceted. The U.S. Department of Agriculture and other groups are urging coffee growers in the watershed’s mountainous region to switch to shade-grown coffee, which is less disturbing to the landscape. A group called Ridge to Reefs is working to stabilize soil on mountain slopes, where heavy rains combined with road-building and intensive agriculture cause significant erosion. Farther downstream, efforts are underway to upgrade wastewater treatment to capture more nitrogen and phosphorus. Plans are in the works to restore the Guánica Lagoon, which served as a natural sponge to filter pollutants before they could reach the bay.

Whitall said he hopes to repeat the study in five years to gauge the effect of the restoration work.

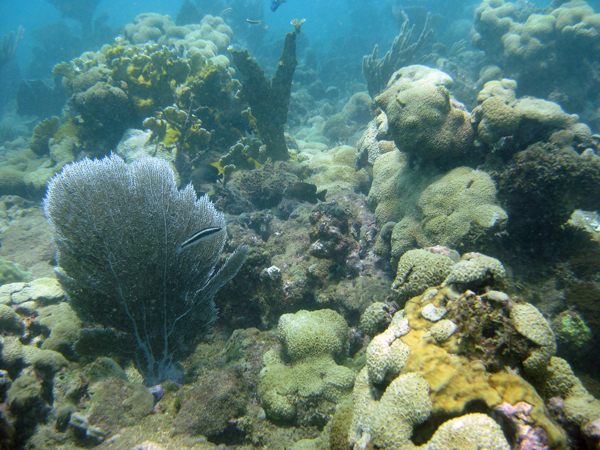

Coral reef near Guanica Bay (Credit: NOAA)

Created in 1986, the National Status and Trends program uses contaminant monitoring in U.S. coastal waters to provide resource managers the background pollution data needed to assess the effects of cleanup efforts and environmental disasters. For example, program data were instrumental in showing changes in the concentration of chemical compounds in Gulf of Mexico water, sediments and shellfish following the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill, Whitall said.

The Guánica Bay study is part of a broader NOAA effort to monitor coral reef health in Puerto Rico’s coastal waters. For instance, a 2007 study began to establish a link between contaminant concentrations and the condition of coral reefs. For a 2009 paper, Whitall and colleagues measured some 150 pollutants in samples of a particular coral species from eight sites across the island’s southwest coast, and found that in most cases the contaminant levels in corals were similar to levels in the surrounding sediment.

NOAA also performed an ecosystem assessment around Vieques, a Puerto Rican island that the U.S. Navy “basically bombed into next week” when it was a training range, Whitall said.

0 comments