Regional Lake Monitoring in Maine: Community Funded Research and Protection

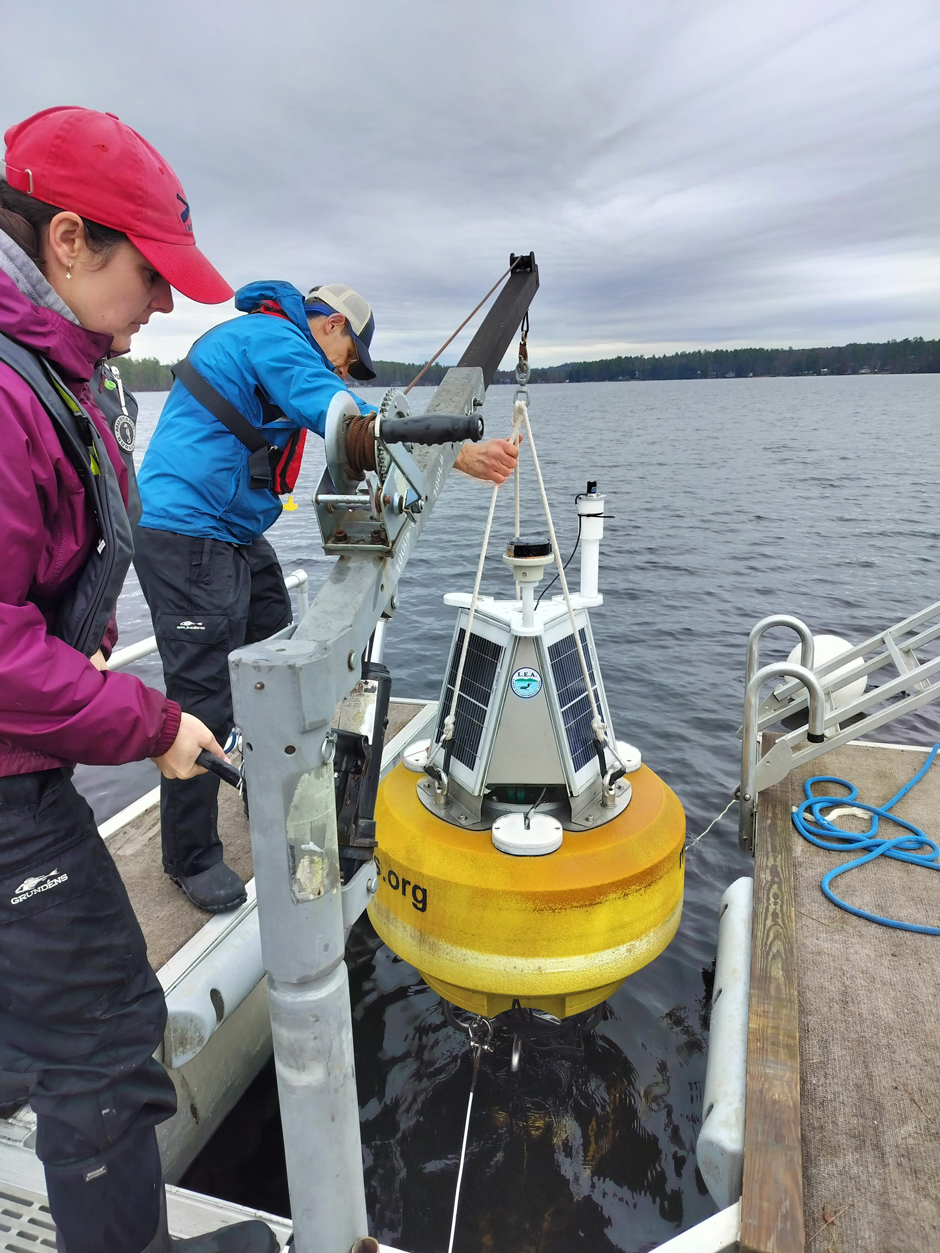

LEA Staff Limnologist Maggie Welch on board buoy boat as it approaches Long Lake deployment site (Bridgton/Harrison, ME)(Credit: Ben Peierls / LEA)

LEA Staff Limnologist Maggie Welch on board buoy boat as it approaches Long Lake deployment site (Bridgton/Harrison, ME)(Credit: Ben Peierls / LEA)Lakes everywhere are threatened by climate change, harmful algal blooms, invasive species, and other environmental stressors. Local, regional, and federal agencies have stepped up in order to defend the environment and water resources. The Lakes Environmental Association (LEA) in Maine is one example of an organization dedicated to protecting local freshwater resources.

Dr. Ben Peierls, LEA Research Director, explains the history of the nonprofit, “For more than 50 years, [LEA] has been working locally, statewide, and regionally, helping or interacting with people on lake water quality, watershed protection, conservation, education, invasive species, and other issues.”

Peierls’ position was created when LEA set out to enhance and grow their scientific efforts—essentially building upon the research that was already being done on the lakes. Having worked on limnological research in New England right after his undergraduate degree, Peierls was drawn to LEA’s mission and focus.

Lake Monitoring Efforts in Maine Lakes

Based in Bridgton, Maine, LEA currently monitors 41 lakes in the surrounding region. All six towns in the area and some local lake associations help support LEA’s monitoring efforts.

Some of the lakes are monitored with real-time systems, though a majority of them are monitored through discrete sampling efforts. Local volunteers sometimes assist in conducting spot sampling. About half of the lakes are monitored throughout the summer season (May through September), and the rest are sampled once a season. LEA staff compile the data for use in trend analysis and other research questions.

LEA Research Director Ben Peierls measuring surface water conditions on Moose Pond (Denmark, ME) using a YSI EXO2 sonde and flow cell. (Credit: Ben Peierls / LEA)

Peierls expands, “What we’re doing is monitoring the current conditions and any long-term changes to the lakes in terms of basic, but important indicators that are used by the state and nationally for judging lake trophic state.”

The indicators involve three primary measurements: water clarity, total phosphorus, and chlorophyll. In addition to these foundational parameters, LEA also conducts high-frequency data collection using temperature logger arrays (Onset HOBO Pendant Temp/Light Loggers) that are deployed in over a dozen lakes during the open water season and, in some cases, through the winter. Data from the loggers are collected at the end of the season when the sensors are retrieved for data download.

LEA also uses two automated NexSens CB-450 buoys equipped with X2-CB Data Loggers—one on Highland Lake and the other on Long Lake. The systems collect data every 15 minutes, reporting lake conditions in real-time. Data collected by the attached In-Situ RDO Blue sensors, Turner Designs Cyclops-7 chlorophyll fluorometer, and LI-COR LI-190 and LI-192 Underwater PAR sensors are pushed to the cloud and stored in the WQData LIVE datacenter.

A nearby, centrally located meteorological system collects weather data that pertains to the two lakes and allows LEA to analyze the influence of climate on water quality conditions. The data buoys provide a much more detailed image of lake conditions compared to the discrete sampling program, which collects measurements and samples every two weeks.

LEA Staff Limnologist Maggie Welch starting a profile using a YSI EXO2 sonde on Long Lake, Harrison, ME. (Credit: Ben Peierls / LEA)

In addition to monitoring primary water quality parameters, the LEA team is working to study other limnological questions and emerging concerns like phytoplankton community dynamics, toxic algal blooms, fecal source tracking, microplastics, and PFAS.

Peierls elaborates, “We have some of the instrumentation and the capacity to do this—and this information is really critical. We provide information to local towns, landowners, and the general public.”

The staff at LEA’s Science Center perform phosphorus and chlorophyll analyses on collected samples, communicate and educate the public on lake conditions, and manage the maintenance and deployment of monitoring equipment. Data gathered by the buoys and spot sampling initiatives all support trend analysis and a larger data pool.

LEA also provides data to national research efforts as the organization has years’ worth of data to lean on. While local lake quality is good overall, climate change and other environmental stressors are ongoing threats to Maine resources. Long-term monitoring can help oversee and document these changes.

LEA buoy moored at site on Highland Lake, Bridgton, ME. (Credit: Ben Peierls / LEA)

Challenges for Local Lake Groups

While the Bridgton region is fortunate to have relatively pristine lakes, the seasonal freezes and thaws can make monitoring difficult. Equipment like the temperature loggers are able to be left in the lake during the winter. However, data buoys and other surface equipment can be damaged if frozen into the lake ice, limiting winter data availability. To help fill that gap, LEA staff have been visiting local lakes in the winter for the last several years to collect samples and water column profiles using a YSI EXO2 sonde or YSI ProSolo handheld ODO/T sensor.

Peierls also has to consider what data is necessary in regard to lake dynamics when designing monitoring systems and initiatives. While Maine is certainly not known for being plagued with algal blooms, lakes in other parts of the state have started to experience them on a more regular basis.

Only a few lakes in the LEA network have experienced bloom conditions in the past, so monitoring efforts center on conditions that may lead to algal blooms and tracking potential bloom formation. Chlorophyll and PAR monitoring are included in the suite of sensors attached to monitoring buoys—both of which are used to provide an early warning for changes in algae and water clarity.

EXO2 sonde in flow-through mode using flow cell (covered in towel) as it collects surface water quality data. (Credit: Ben Peierls)

While the sensors on the buoy provide a good snapshot of data, they can only monitor the water column at a single site on the lake. The use of autonomous surface vehicles (ASV) and other moving surface monitoring equipment could provide more insight into surface conditions across the lake.

Peierls has developed a system that collects data from a moving boat using a YSI EXO2 sonde in a flow-through configuration. Like an ASV, however, this device provides surface measurements only, missing changes that occur deeper in the water column.

While vertical, horizontal, spatial, and temporal monitoring can all be conducted separately with various innovative pieces of equipment, Peierls has to consider the cost of such instruments. The initial purchase and continued maintenance are important considerations when developing a monitoring initiative—details that shape the system and data availability.

The buoys do provide continuous data, and maintenance is relatively simple, with removal occurring each winter and redeployment in the spring. Data flow pauses and alarms make it easy to identify when a sensor has failed, and Peierls can head out into the field to assess the equipment.

Maggie Welch prepares to head out for buoy deployment. (Credit: Ben Peierls / LEA)

Conclusion

Peierls and the LEA team spend the monitoring season visiting sites, performing spot sampling, analyzing samples, reviewing data, and preparing summary reports of current water quality conditions and trends. Working as a team allows LEA to monitor the 41 lakes in their region and effectively work with the public, state agencies, universities, and other nonprofits.

Having come from a background in academia, Peierls found the change to working at a nonprofit refreshing. He explains, “LEA members are incredibly supportive financially and in other ways like volunteering. We live and work around these beautiful natural systems, and it is so encouraging to get feedback from members who are so excited that we’re working to protect and understand these lakes.”

He continues, “It’s just been incredible. At my age—I’m not quite at the end of my career, but you know, looking towards the end of my career—it’s been really energizing to do this. Just seeing how many people are so generous, and they’re always telling me, ‘Keep it up, we really love what you do.’ And that really applies to the whole organization.”

The success of monitoring efforts and lake protection rests on the shoulders of everyone at LEA who has worked in the area for over 50 years. Teamwork and a group of dedicated staff are the keys to covering the various lakes, watersheds, and freshwater systems in Maine.

Peierls concludes, “We have many different tasks and things that we do to respond to the issues with lakes, watersheds, and water quality—the projects and solutions are all driven by the amazing people that work here.”

Ben Peierls and Maggie Welch prepare to release buoy on Highland Lake. (Credit: Rachel Harper / LEA)

0 comments