Researchers Develop Handheld Water Quality E. coli Sensor for Real-Time Results

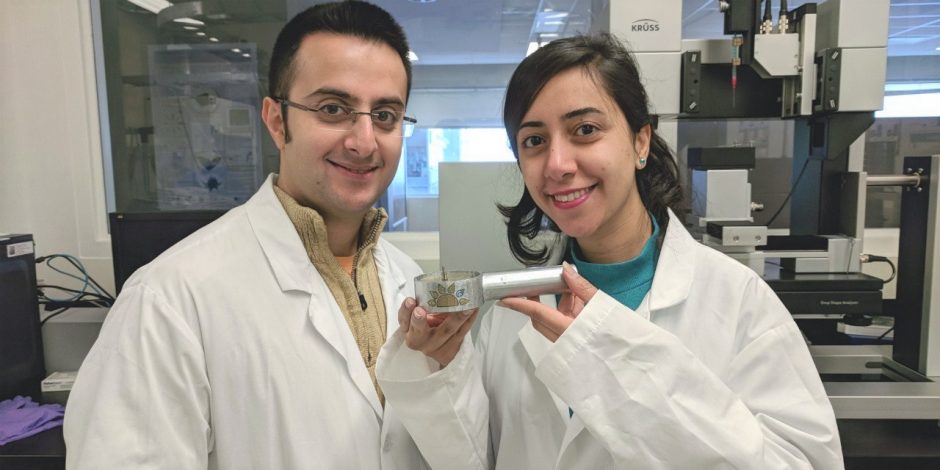

Parmiss Mojir Shaibani and Amirreza Sohrabi holding their device. (Credit: University of Alberta)

Parmiss Mojir Shaibani and husband Amirreza Sohrabi have together taken an innovative approach to creating solutions for communities that lack access to clean water. Their latest project has resulted in a handheld water quality sensor that can provide real-time results on the presence of E. coli for users, eliminating the need for lab processing, and reducing costs substantially.

“Both Amir and I were working on our Ph.D. projects related to water,” explains Dr. Mojir Shaibani. “We realized that around the world approximately 4,000 children, sadly, die because of contaminated water. Assuring the safety of water becomes very important, especially in more remote areas. Moreover, we are from a country, Iran, where sources of potable water are scarce in many regions. We were taught the value of clean water from childhood. These all inspired us to focus our endeavors on clean water and solving problems that hinder the access to this precious resource.”

Real-time results

One of the pain points that seemed most important to the researchers and demanded resolution was the need for real-time results and the elimination of traveling to a lab and waiting for answers. Current testing methods see a delay of up to one week between water source sampling and delivery of final results, and this delays any decision-making process.

“This delay can be catastrophic if a population consumes the contaminated water while awaiting results,” asserts Dr. Mojir Shaibani. “The Walkerton incident taught us that.”

The Walkerton incident in the year 2000 is known as the worst E. coli outbreak in Canadian history. The incident saw more than 2,300 people fall ill and 7 people die after consuming water contaminated with E. coli. Authorities scheduled routine sampling and testing of the drinking water source on the same day that the population of the town showed the first symptoms of the sickness. The samples were transported to a lab and the results were ready two days later. It was those two days that caused the real outbreak of the illness and the unfortunate death of 7 people.

“Although this was a single incident, the timeline of the events has taught us a lot,” remarks Dr. Mojir Shaibani. “If there had been a way to avoid the delay by testing the water rapidly onsite in Walkerton, the whole incident could have been avoided.”

Handheld sensor

The device. (Credit: Roshan Water Solutions)

The device is an electrochemical sensor that works based on the metabolic activity of the E. coli. The surface of the electrochemical electrode is nano-engineered to be specific to the metabolic activity of E. coli bacteria. In other words, even if the E. coli is present within a mixture of different species, only the E. coli can stick to this particular electrode’s surface based on its unique metabolic activity. This selectivity is crucial to avoid interference from other species and false positives.

This is the second iteration of the device. At the moment, two main parts comprise the prototype: a reader and a cartridge. The reader contains all the necessary electronics for doing the measurements, performing necessary computation on the signal, displaying the final results, and sending the data to the cloud for further analysis. The reader also contains a rechargeable lithium ion battery to power the electronics.

The cartridge is pre-packaged with all the necessary electrodes, including the nano-engineered electrochemical electrode that reacts with the E. coli. The cartridge will need to be replaced after use, but the reader will be a one-time purchase for users.

As the team studied existing methods for water testing and evaluated the gaps in the system so they could create the prototype, they identified several gaps in the current standard and other innovative testing methods. They were laboratory-based, required a long analysis time, at least overnight, and they were too expensive to be accessible to everyone.

“The current standard method of testing for E. coli is a laboratory-based test that requires sample transportation, highly skilled personnel, and standard equipment,” explains Dr. Mojir Shaibani. “Moreover, this method requires the overnight culturing of samples in a food-based media at the right temperature, so the bacterial colonies can grow and be counted. There are a few new technologies out there that either are the miniature version of the standard laboratory tests or new portable devices; however, they are expensive. Our device will bridge these gaps by enabling the test onsite and in less than one hour. Also, the price of the device is predicted to be in the range of $150-300 per reader and $15-30 per cartridge.”

Diagram of E. coli interacting with sensor. (Credit: Roshan Water Solutions)

Eventually, the team hopes that their device will reach rural areas in developing countries—and they are working to ensure that it will be accessible in these areas.

“There is great potential for our device in rural communities and developing countries due to the fact that the current standard method is not suitable for these regions,” Dr. Mojir Shaibani states. “So, this device can be really helpful in these regions, and we are aiming to introduce the technology in the future. However, modifications will be needed to lower the price.”

“At the moment we are working with the University of Alberta eHUB, a space for entrepreneurs, and receiving help from their Rural eHUB program to help rural communities,” adds Dr. Mojir Shaibani.

0 comments