Satellite data show Maine lake clarity grew murkier in past 15 years

Knowlton Pond is among Maine's 5,500 lakes and ponds larger than 1 hectare (Credit: Ian McCullough)

Maine may not have Minnesota’s license plate bragging rights when it comes to the state’s number of lakes. But the northeastern state has enough lakes to make manually gathering enough data for a statewide look at water quality into a tall order.

“They say on the license plate, “Minnesota: Land of 10,000 Lakes,” said Ian McCullough, lead author of a recently published study on water clarity in Maine. “Maine doesn’t have quite that many, but I think it has a lot more lakes than people think.”

In an effort to include as many of those lakes as possible–even the remote ones scientists rarely access–in regional water quality assessments, the state turned to satellite data that can be used to estimate lake clarity. The results of a study using the data published online in June by the journal Freshwater Science show that clarity in the state’s lakes decreased on average by around half a meter from 1995-2010.

McCullough, now a doctoral student at the University of California Santa Barbara, led the study as a masters student at the University of Maine. He said that water clarity is highly correlated with other water quality metrics like chlorophyll and phosphorus, but is much easier and cheaper to measure. That makes it an ideal parameter for local volunteers and students to track because they can easily be trained to use a Secchi disk to collect clarity data.

While volunteer-based clarity measurements are reliable for tracking the health of individual lakes, the aggregated data from a state’s citizen monitoring program might not necessarily be representative of water quality across the region. That’s because the lakes under those programs are generally monitored for a reason, rather than at random.

“People tend to sample lakes near roads or near places that they live,” McCullough said. “A lot of times the lakes closer to human development are the ones that that are more likely to be impaired, but that’s not always the case.”

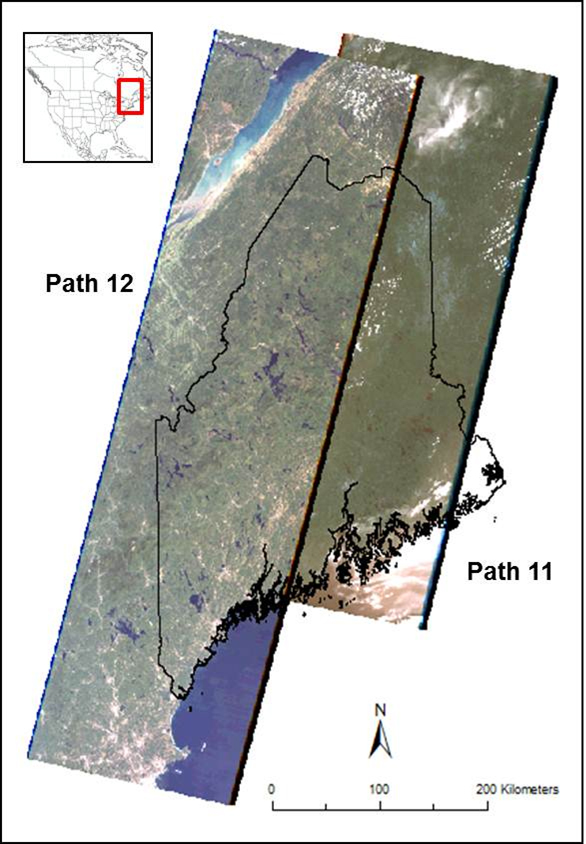

As a result, remote lakes can be underrepresented in a statewide sample. McCullough and his coauthors turned to data from the Earth-sensing Landsat satellite program, which measures electromagnetic radiation, among other things. The researchers isolated data the satellites’ sensors recorded as they passed over Maine from 1995-2010. To estimate lake clarity, the focused on the blue and red sections of the visible portion of the electromagnetic spectrum.

“Blue is correlated with very clear water and red is correlated with murky, algae-filled water,” McCullough said. “We can combine those two signals to estimate the Secchi depth of the lake.”

The researchers used two overlapping paths from the Landsat satellites to reduce cloud interference (Credit: Ian McCullough)

Though the resolution of the satellite sensors limited their assessment to lakes larger than 8 hectares, the researchers were still able to estimate the clarity of more than 1,500 lakes over the study period, McCullough said. That’s much better coverage than the state’s field assessment program. For example, the researchers estimated clarity of 633 lakes for the year 2010. The field program only had data for 71 lakes over the same time period.

The study found that on average, the clarity of lakes across the state declined by around half a meter. McCullough said a half-meter fluctuation in clarity isn’t unprecedented, but it’s a trend worth tracking, especially with the potential for warming temperatures and longer growing seasons associated with climate change to increase algal growth.

“This is not a very large decline, but we think it’s something that state managers and lake associations should be aware of,” he said. “We just wanted to let people know that this is potentially a sign of things to come.”

Though satellite data can provide wider coverage of Maine’s lakes than a field monitoring program, it’s no replacement for the data collected by the states dedicated volunteers, McCullough said.

“They are the ones that collect the majority of the data that we used at the university to calibrate our models to estimate water clarity across the state,” he said. “This is a really good example of the impacts that engaged citizen scientists can have on scholarly research, and ultimately policy and management of natural resources.”

Top image: Foss and Knowlton Pond is among Maine’s 5,500 lakes and ponds larger than 1 hectare (Credit: Ian McCullough)

0 comments