Science Near the Salish Sea: Friday Harbor Laboratories

Less than four hours away from Seattle and Vancouver is a different, less urban sort of gem: the University of Washington (UW) Friday Harbor Laboratories (FHL). In the midst of the Salish Sea, FHL is a truly unique setting for marine research. Director Billie Swalla spoke with EM about this biological field station set up for exploring the rich and varied ecosystems of the San Juan Archipelago.

“We’re a research unit with the University of Washington, part of the College of the Environment,” explains Dr. Swalla, a biologist. “Our main mission is marine research, with teaching and outreach a close second and third after that. And of course, teaching those research methods and outreach to the local community are also priorities.”

Most marine labs or biological field stations are on permanent sites that are either very unique from an environmental science standpoint, or located in biodiversity “hotspots.” Both are true for FHL’s location.

The research vessel Centennial, sits at the dock. (Credit: Friday Harbor Laboratories, via source)

“UW Zoology Professor Trevor Kincaid came up the coast, went inland, and found this site, and realized how high the biodiversity is,” details Dr. Swalla. “We have more biodiversity here than we actually do on the outer coast because of the different habitats in the San Juan Islands. Marine invertebrate larvae settle out here that have been traveling in the open ocean.”

Home for students and teachers, both

FHL is set up to support a fairly extensive range of both research projects and teaching, based on both its size and amenities.

“We’re a pretty big marine lab as far as they go,” comments Dr. Swalla. “We have 100 beds for students and 100 beds for scientists, so 200 beds total. 100 beds for scientists include housing for families, so there’s probably room for 30 or 35 researchers at a time. From June 1st to probably the end of September we’re full. We have University of Washington undergraduates in the spring and fall.”

In the summer FHL also features graduate programs and research experience for undergrads. Many students at UW who study at the field station find themselves returning.

“Many people here are primarily doing research,” Dr. Swalla describes. “Some of the classes are teaching and then also have a research component. A lot of undergraduate students that come here first start their project as a class project, and then come back year after year to work here.”

This continuity comes, in part, from generous funding and mentoring support.

Friday Harbor Laboratories, 2019. (Credit: Friday Harbor Laboratory, via source)

“We are very generous with raising money for students, and we have a number of full student fellowships,” comments Dr. Swalla. “We gave out 25 graduate fellowships last year for summertime work. There’s an independence that comes with them; fellows are working with an advisor, but they have an independent project that they can pursue on their own.”

Research at Friday Harbor Laboratories

Students, visiting researchers from around the world, and UW faculty study biology, chemistry, ecology, oceanography, and other marine disciplines at FHL.

“We do everything from cellular and molecular biology to studying neurons and how patterns evolve, to studying ecosystems, to more applied work like seagrass restoration,” remarks Dr. Swalla. “Doctor Adam Summers, who’s in biology and the School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences (SAFS) is behind one of our big programs.”

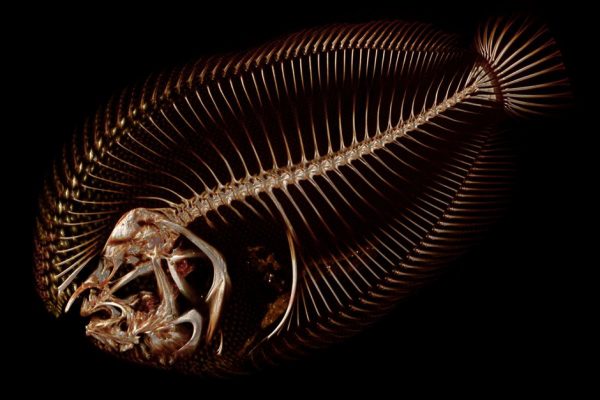

Dr. Summers’ research interest is in functional morphology of fishes and fish ecology.

“The project is called ScanAllFishes, and it aims to scan all 35,000 or so species of fish with a CT scanner” states Dr. Swalla. “Once scanned, we look at the teeth structure, the bone structure, the gills, the vertebrae, to identify patterns and how morphology is evolving. How do those features affect the way that the animal lives?”

The FHL team has expanded that project, even using other medical scanners on our campus to scan larger specimens like sharks.

Another FHL program centers around Dr. Jim Truman and his work that originated in part at Janelia Farms.

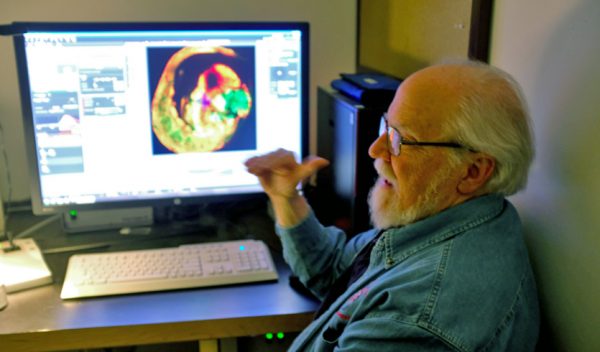

Jim Truman with the confocal. (Credit: Friday Harbor Laboratories, via source)

“Dr. Truman’s previous work looked at how insect hormones affected metamorphosis and evolution and development,” explains Dr. Swalla. “Insects are now considered part of the group called pan crustaceans, so the project is now focused on looking at crustaceans to see whether it seems that the same pattern happened in crustaceans as it did in insects. They have found that crustaceans have the same 30 pairs of stem cells, which is kind of cool because there’s a lot of evolutionary time that elapsed there.”

Ocean acidification is another research area for the FHL team.

“We have some instruments that are 10 feet below dock and some at a deep spot, down around 90 feet,” states Dr. Swalla. “That’s because we know from our previous experiments that below about 80 feet it doesn’t change much. At the top, there’s a lot of change in temperature, pH, and dissolved oxygen in the water.”

The team is now working to allow their instruments to “talk” to users and make their data available online for easy downloading.

“That should provide a long-term look into what the conditions are out here most of the time,” adds Dr. Swalla. “When we get these upwelling events that happen, what happens when you get the pH suddenly going down really low? You have to take one variable at a time. As we have these warming trends, it’ll be really interesting to see how that affects these biological processes.”

Dr. Swalla is currently researching cell development and classes of regeneration.

CT scanned Hammerhead. (Credit: Jim Truman)

“We work with acorn worms that completely regenerate themselves when cut in half,” details Dr. Swalla. “We think in terms of gene networks, not just single genes. Transcription factors are genes that turn on other genes. Our challenge is to look at these particular networks to try and figure out what is allowing the worms to ‘turn on’ the regeneration process.”

Why bother? Because ultimately if researchers can learn which mechanisms allow worms, for example, to be cut in two and “regrow” entire new heads and organs, they might eventually learn how to regenerate damaged tissues and organs in humans, too.

“One of the good things about using invertebrates as far as embryonic development goes is that most of the animals will spawn right into the water,” remarks Dr. Swalla. “You can get lots of embryos and then try to figure out what’s going on with their gene networks, and then take that information and try to apply it to other animals.”

A vision of the future

In some ways, what comes next for FHL is easy: more of the same.

“Our lab is very well known,” states Dr. Swalla. “Most people who have done some work in marine science have taken a course here, come to events here, or worked here. As I go different places as director, I hear people say, ‘Oh I love Friday Harbor Labs,’ or ‘Oh, I spent a summer there, it was fantastic,’ and people have a real love for it. We find that our people are all over the world.”

Even so, the team is hoping to expand and offer more to the researchers and students that spend time at FHL.

CT scanned flatfish. (Credit: Jim Truman)

“We’re trying to raise money for a new building because we’d like to be able to house all the people that are here in one place,” remarks Dr. Swalla. “This way we can have lectures and larger events. Our biggest lecture hall right now holds 85 people.”

The connective tissue that holds every project and participant together at FHL is a love for the work and an interest in getting it done. Dr. Swalla takes pleasure in encouraging the next wave of would-be researchers to keep studying and to come to FHL.

“It’s maybe a little bit cliché, but it happens all the time,” laughs Dr. Swalla. “Whenever I meet students that say, ‘Oh, I wanted to be a marine biologist but I ended up being an accountant,’ or something like that, I say, ‘Well, you could go back and be one today. It’s a good job. You could go back, get some higher education and teach.’”

0 comments