Small But Mighty: Tijuana River NERR Makes the Most of Reverse Estuarine System

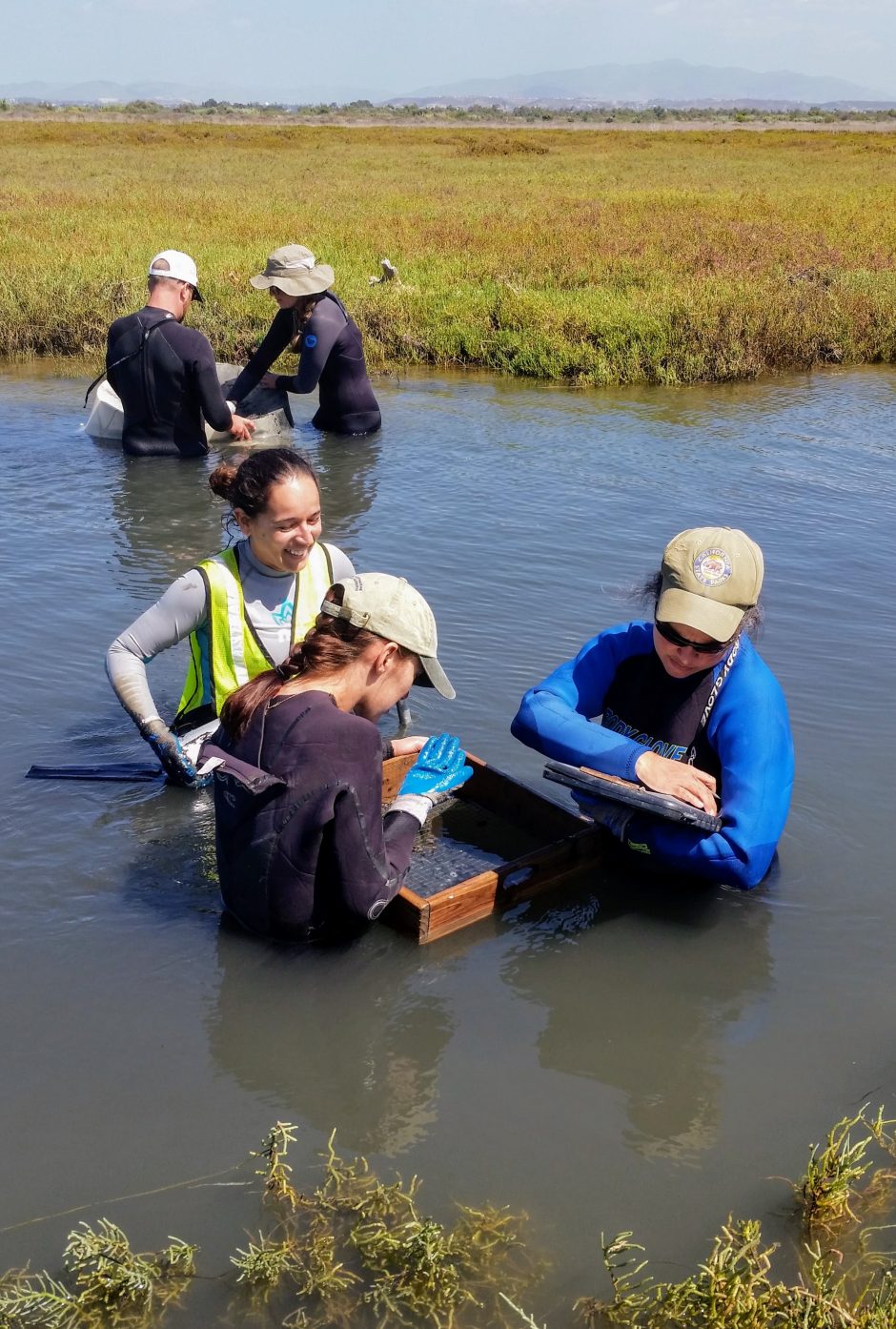

Inverts: Tijuana River NERR monitoring crew. (Credit: Marya Ahmad)

While every one of the 29 National Estuarine Research Reserves (NERRs) in the U.S. has features that define it, Tijuana River NERR has some characteristics that may be unique. Jeff Crooks, the research coordinator at Tijuana River NERR, has been exploring the NERR since his days as a student in the 80’s when he was at San Diego State. He also worked for Professor Joy Zedler of San Diego State University. “There aren’t many places like Tijuana River NERR,” he says. “For one thing, it’s probably one of the few estuaries where the river is dry much of the year.”

Tijuana River NERR is located in Southern California, near the city of Tijuana. Tijuana River gets very little rain from March to October, and is like a desert environment in some ways. Typically only ten inches of rain fall per year. “Something that’s interesting about it is it’s a place where desert meets ocean meets freshwater. Since it’s dry much of the year, we can think of it as a ‘reverse estuary’ in a sense,” Crooks explains.

In addition to his duties as research coordinator, Crooks is also the chair of the System Wide Monitoring Program (SWMP) Oversight Committee in which all NERRs participate. “Collecting the SWMP data is absolutely critical to getting the pulse of the NERRs and keeping track of their health,” says Crooks. “About 70 percent of our funding comes from the federal government through NOAA, and the other 30 percent comes from the state. It’s great that we get not only state but national support too.”

In Tijuana River there are four core SWMP sites, with four additional sites. The same SWMP protocol is used for all sites. Three of the monitoring sites are located in the Tijuana estuary, two are close by in San Diego Bay, and three are in the Los Peñasquitos Lagoon (in Torrey Pines State Parks).

Like the other NERRs, Tijuana River uses a Campbell Scientific weather station that employs telemetry. A Sutron system is used. Los Peñasquitos also has a deployed camera system. There is a GOES system that sends data to a satellite. YSI EXO-2 sondes are used for water quality data.

Torrey Pines also has a camera system that snaps pictures of the area. These pictures make it possible to monitor the tidal exchange at the inlet. Tidal exchange pictures are streamed to the web page, set up with the help of Hound systems. The Central Data Management Office (CDMO) does not handle the camera data, but it does handle all the formal SWMP sites’ data. The CDMO is located at the University of South Carolina, and its data can be downloaded by the public.

Bathy River Surveyor: Justin McCullough. (Credit: Jeff Crooks)

The secondary SWMP sites at Tijuana River NERR are treated just like SWMP sites in terms of how data are gathered.

“The SoCal system is pretty small compared to, say, the East or Gulf Coasts,” says Crooks. “But it has some unique features that are worth experiencing. It’s a geologically active coast that acts like desert much of the time, and a unique feature here is the behavior of the sand bars, which change and influence everything around them.” Sand bars naturally occur in many places close to the ocean. In Tijuana River, human activity has made it more common for sand bars to close, and for the river mouth to close. “The watershed input becomes really dramatic when the mouth closes,” says Crooks. “Anoxic areas can be created, and sometimes large fish kills can happen.”

While it may seem like there is no way of preventing these mass kill events, Crooks explains there is something they can do about Tijuana River NERR to help wildlife, but it has to be done at just the right time: opening the mouth of the Tijuana River. “We have the ability to open the mouth of the Tijuana. We try not to do it very often though, as it costs thousands of dollars. Heavy equipment is needed to excavate the mouth, and that gets expensive,” he explains. Not only is it costly to open the mouth, but weather effects can make an opening ineffective if the mouth is opened too early. “This time of year we have winter storms moving sand offshore, where it builds up. Now would not be a good time to open it,” he says.

While oxygen levels are usually good during the day, even if the mouth closes, the problem is that the oxygen levels plummet at night, when the estuarine vegetation and algae is no longer photosynthesizing. “That’s when you can get large fish kills, such as sardines and smelt,” Crooks explains. “Luckily the Tijuana mouth doesn’t close very often.”

In 2015-2016, however, there was a severe El Niño and the Tijuana River mouth did close. Prior to the 2015-2016 season, it had not closed since 1984. “We thought of it as a good preview of climate change to come,” says Crooks. “We saw the sea level increase by a whole foot, and big waves. We actually thought at the time that a water level rise might help conditions at Tijuana River. We thought it might help flush the area out and keep the mouth open. That didn’t turn out to be the case.”

Instead of helping the estuary, the water rise caused beach sediments to come in, and a significant amount of wetland was lost. “While it’s normal to get some sediment coming in, the water rise just made it much worse,” says Crooks.

While the Tijuana River mouth can be opened, there are other methods Crooks and his colleagues can use to combat sediment effects and protect wetlands. “We try to restore tidal flushing through restoration of intertidal habitats, which helps keep the mouth open,” he says.

Though Crooks and his colleagues keep a close eye on Tijuana River conditions, they can’t always prevent tragic events. “There was a time when the system went anoxic over the weekend, and dozens of leopard sharks died. Species can often survive anoxic conditions for awhile, for example at Torrey Pines we’ve had times when it’s gone anoxic for a few days with no big effects. But if it goes on too long we can see large die offs. Stratification of freshwater and salt water can happen in the estuary, for example, and that can lead to oxygen availability problems,” says Crooks. While weather, climate and sediment movement can play roles in anoxia events, pollution discharge can also be a factor. The Tijuana River NERR area does experience sewage discharge from the considerable population of nearby Tijuana. Too much can push the estuary into anoxia.

Fishing: Tijuana River NERR monitoring crew. (Credit: Marya Ahmad)

While the Tijuana River NERR conditions can be tough on wildlife, the conditions can be tough on researchers trying to gather data from the NERR, too. “Sometimes the placement of instruments is tricky because we don’t want to place them in areas that are going to become clogged with sediment. Probably most of the NERRs don’t have to deal with that issue,” Crooks mentions. “Most data loggers are placed a half meter off the water bottom for SWMP purposes, but many of our areas are too shallow for that.” Floating sondes might address the low water levels. In addition, Crooks and colleagues would like information on more of the water column than what is typically covered in the SWMP protocol.

As Crooks and his colleagues have watched, Tijuana River NERR has been influenced more and more by the explosive growth of the population of Tijuana upstream. “We have a big watershed, over 1700 square miles,” says Crooks. “In the past 20-30 years we have seen huge growth of the human population and how that affects everything that happens downstream. Great swaths of vegetation get denuded and that leads to considerably more sediment traveling down the river, to where we are.”

In Tijuana, the booming population means many are struggling just to survive and set up housing. Some residents even use old tires filled with dirt as a basis for house foundations. Though typically people are thought of existing in opposition to wildlife, in Tijuana the people and the wildlife both wrestle with the sometimes harsh environment.

“We try to come up with creative ways to deal with the challenges here. We are always looking for win-win solutions, where people win but the wildlife and the estuary win, too,” says Crooks.

One of the innovative ways people have come up with for dealing with increased amounts of sediment from Tijuana is by creating a big sediment catch basin, which basically is a large hole into which 50-60,000 cubic yards of sediment falls, instead of going up to the NERR and possibly causing wetland loss or river mouth closure.

“There are many reasons we need to protect the Tijuana River NERR,” Crooks emphasizes. “For example, we have the second largest population of Ridgway’s rails (also known as clapper rails), which are a threatened species. We also have the largest most intact wetland in southern California.”

Crooks believes that looking for win-win solutions that involve the community of Tijuana will ultimately be the best approach for protecting the NERR. “Many of the people have arrived in Tijuana because there are jobs. They are doing whatever they can to just eke out a living on the hillsides. What we want to do is encourage them to build but in ways that minimize the impact on the environment, like planting native vegetation to try to stabilize slopes. Also we think there are ways to use landforms that are already there to create a workable system.”

There are already some big restoration projects to try to recreate previous wetland habitat and functionality. These efforts try to go beyond measures such as dumping sand on marsh beaches.

While Crooks is involved in restoration projects and environmental monitoring, there are also two other staff and five to six other part time researchers who also participate in supporting the NERR. In addition to SWMP efforts, extensive bird monitoring takes place during quieter parts of the year, in the fall and summer. The threatened Ridgway’s rail creates floating nests in the marsh which staff monitor. Savannah sparrows nest in the high marsh, while least terns, snowy plovers, and pelicans can be found near the beach. “I even saw a runaway flamingo once,” Crooks adds. “It’s a huge area for birds. Great for bird watching.”

And if that isn’t enough, Tijuana River NERR even has halibut nurseries.

“It’s a special place here,” Crooks reflects. “It’s a slice of nature in a pretty urban area. We always ask how we can preserve slices of nature like this. I’m a big advocate of win-win scenarios. I think if people are introduced to these areas and how special they are, they will start to think of ways we can coexist with them, ways that people win and the estuary wins too.”

0 comments