When upgrading satellite-based snow cover estimates, work starts on the ground

Installing gridded arrays of temperature data loggers to monitor the fraction of snow cover on the ground, crucial for validation of Landast and MODIS-derived snow cover estimates. (Credit: USGS)

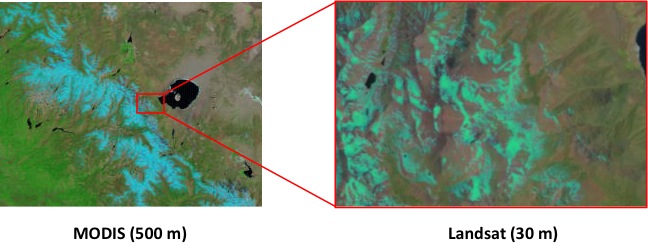

Satellite-based measurements of the area of snow covering a given landscape is important information for water managers, ecologists and climate scientists. U.S. Geological Survey researchers are working on improving the tools that collect that data, sharpening up the resolution from 60 football fields to a couple end zones.

NASA already produces an estimate of snow cover based on data collected by the MODIS optical imaging instruments aboard the agency’s Terra and Aqua satellites. But that sensor operates an a resolution of around 250,000 square meters per pixel, or a little more than 60 acres.

“In terms of the variability we can see in snow cover, that’s actually quite large,” said David Selkowitz, a research geographer with the USGS Alaska Science Center.

On the other hand, the sensor aboard the USGS Landsat satellites captures images at a resolution of a 900 square meters per pixel. The drawback is that while the MODIS instrument can deliver new data from any site once a day, the Landsat data is limited to once every 16 days.

“You get a more sporadic picture, but when you do get a picture you get a more detailed picture,” Selkowitz said.

One hurdle the researchers will have to overcome is that the optical sensors, which operate in the visible and middle-infrared ranges, can’t see through tree canopies. That means the data will take some extra processing in order to account for snow in forested areas that isn’t visible from the air.

As an early step toward gleaning the extent of snow cover under canopies from satellite data, Selkowitz is working with ground-based sensors to analyze snowmelt under a variety of forests throughout the mountainous West.

This illustration shows the finer scale achievable with the Landsat sensor over the MODIS sensor (Credit: USGS)

The researchers are using grids of temperature sensors to detect snow cover in forested and open regions in the mountains of Utah, Colorado, California, Washington and Alaska. Grids of 16 temperature sensors and measuring 60 meters on each side–a little larger than a Landsat pixel–are deployed before the first snowfall and retrieved after melt.

The sensors are buried a few inches deep to keep them away from curious passersby, human or otherwise.

“A lot of the areas where we have these I suspect people never wander through, but a few of them are in areas near hiking trails and such,” he said. “But really the bigger danger is rodents and ground squirrels and marmots and animals like that that might decide to carry them away.”

The sensors collect temperature hourly, which the researchers convert into a daily time series of snow cover. It’s a pretty simple conversion, Selkowitz said, because the sensors that aren’t covered in snow show temperature variations of a much as 10 degrees Celsius over a single day as a result of sunlight and weather patterns.

That’s not the case with snow-covered sensors.

“As soon as you get snow on the ground, as long as it’s deeper than just a few inches, that variability is severely dampened to the point where sometimes you get less that half of a degree of temperature change within a day,” he said. “It almost looks alike a heart rate monitor where someone’s dead and as soon as the snow goes away they come alive.”

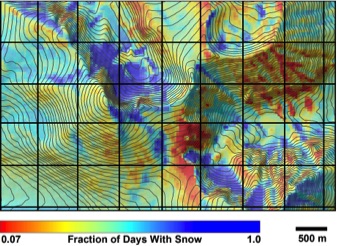

The image above indicates the fraction of days from all cloud-free Landsat scenes where snow cover was present for an 8 year period, documenting extreme variability in snow cover persistence in rugged alpine terrain. (Credit: USGS)

The research is in its second year of data collection, and the project isn’t yet to the point where the researchers can apply their findings to the Landsat data. So far, their results show snow in forested areas melts out anywhere from a few days to a few weeks later that open meadow sites. That’s “not a revolutionary finding by any means,” Selkowitz said, but it’s also not a given. At a recent meeting of the American Geophysical Union where he presented the findings, Selkowitz said scientists doing similar work at lower altitudes have found just the opposite–that forest areas melt sooner that open areas.

Top image: Installing gridded arrays of temperature data loggers to monitor the fraction of snow cover on the ground, crucial for validation of Landast and MODIS-derived snow cover estimates. (Credit: USGS)

0 comments