Study finds greater African dust health and climate impacts across the Atlantic

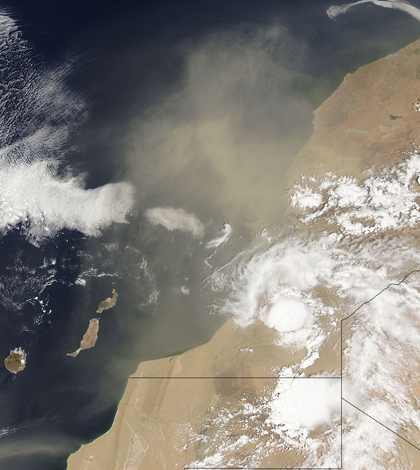

A plume of Saharan dust blows over the Atlantic Ocean from North Africa (Credit: NASA)

During the winter and spring, those who suffer from airborne irritants in South America and the southern U.S. may be choking on a little piece of Africa. A new study from the University of Miami found that high concentrations of dust travel across the Atlantic each year, particularly in winter and spring. This land swap could be harmful to human health and has greater implications for climate patterns worldwide.

“When I first started doing this research, no one had much interest at all,” said Joe Prospero, a professor emeritus at UM’s Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science. “Now when I go to meetings, hundreds of people show up to my talks. There certainly is increasing interest in various aspects of dust transport.”

Prospero has been in the dust game for a long time, so there’s little wonder that attitudes toward his research have changed. In 1966, he studied soil dust in Barbados that had come all the way from Africa. Through the ‘70s and ‘80s, he observed the link between severe drought in North Africa and increased dust transport. Nowadays in Miami, he can spot the subject of his research by looking out the window.

“Every summer here in Miami we have African dust,” Prospero said. “It comes in as a haze. The weekend before last it was very dense.” Florida, he noted, receives most of its transatlantic dust during summer, rather than winter or spring.

The study builds off of Prospero’s previous research, using data and analysis sites obtained over the past several decades. Although Prospero had studied dust transport in many parts of the world, he said that he had been lacking reliable data from the South Atlantic. He found an air quality monitoring site in Cayenne, French Guiana, that would provide the data he needed, and he began to compare it with readings from sites in Barbados.

“Our measurements in Cayenne showed that every spring the concentrations of dust were so high and so frequent that they exceeded the World Health Organization’s standard for respirable particles,” Prospero said. “The rate of exceedance is greater than most cities in Europe where they’re worried about pollution.”

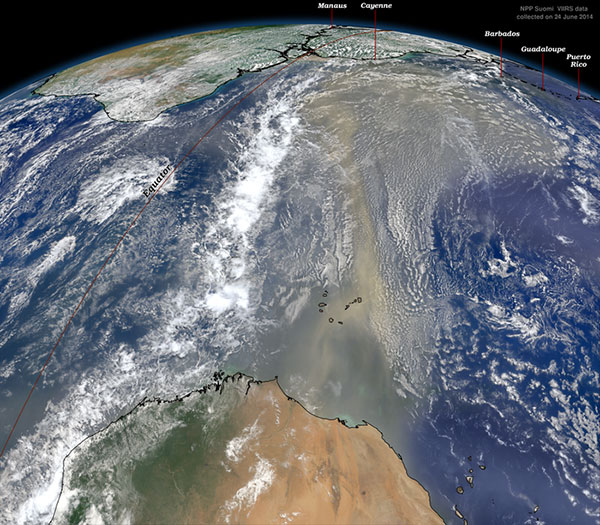

A satellite image shows a plume of African dust soars over the Atlantic towards French Guiana (Credit: Norman Kuring/NASA Goddard Space Flight Center/Suomi NPP)

Furthermore, the measurements showed that large-scale dust events occasionally impacted sites in Cayenne and Barbados at the same time.

Most of this dust originates from the Sahara, a 3.5-million square mile stretch of mineral-rich desert spanning the northern part of Africa. The dust particles are so fine that they can penetrate human respiratory systems and cause serious breathing problems. Some of Prospero’s earlier work found that African dust contributes to concentrations of bacteria and fungi. Other researchers suspect that airborne dust can carry plant viruses, such as the tobacco mosaic virus.

But the effects of dust transport between Africa and the Americas extend beyond the scope of human health. Large clouds of dust can reflect solar radiation, lowering sea surface temperatures that influence many weather phenomena. Satellite imagery has shown that these seasonal dust plumes can interfere with large-scale weather patterns, such as hurricanes or tropical storms.

“There’s no question to us that we’re really dealing with a major dust issue,” Prospero said. “It’s a pretty complex picture, and it certainly isn’t sorted out yet, but that’s one aspect that’s interested a lot of people.”

African dust is beneficial in at least one big way: It’s a major source of iron for the world’s oceans. Iron stimulates phytoplankton blooms, which in turn helps sequester carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

Prospero doesn’t seem too sore that his earlier talks on dust transport were under-attended. He’s understood, for quite a while now, that dust is an important part of many global systems — it’s just taken the scientific community some time to see that.

“Dust is a climate story at many different levels, many different time scales and many different spatial scales,” Prospero said.

North Miami FL lettuce

November 6, 2015 at 6:26 am

It was good!!