Sunscreen Chemicals in Water Can Harm Zebrafish Embryo Development

Dr. Kevin Leung, leader of the research team. (Credit: HKBU, https://cpro.hkbu.edu.hk/en/press_release/detail/91/)

If you’ve ever sat at the beach or on the shore of a lake reapplying your sunscreen and wondered what happens to that sunscreen as it washes off in the water, you’re in good company. A team of researchers has been investigating how sunscreen chemicals affect marine wildlife, and their recent paper indicates that ultraviolet (UV) filters from sunscreen and other personal care products can affect zebrafish embryo development.

UV filters in the water

Dr. Adela Jing Li’s group at Hong Kong Baptist University has been studying UV filters for several years.

“Our first study focused on ecological risk assessment and environmental occurrence of organic UV filters in marine organisms from Hong Kong coastal waters, China; our second study worked on environmental occurrence of UV filters in Hong Kong coastline and its drinking water resources as well as photodegradation of one UV filter and its toxicity,” explains Dr. Li. “With those working experiences and financial support from the mainland of China, we explored our research questions on UV filters further in Shenzhen’s coastal waters, which have never been studied before.”

Dr. Kelvin Sze-Yin Leung, who heads the research team, wondered whether UV filters in combination might be more harmful to marine life than they are when encountered individually. Thus, the team set out to study the chemicals as a group.

“Firstly, UV filters constitute a heterogeneous group of chemicals in sunscreens, makeup, lotions, and other daily-use products,” details Dr. Li. “As a result, they always present as a group in the environment, and their effects on living systems should be evaluated as a group. Secondly, most studies [in the literature] conducted risk assessments on a single compound and concluded that individual sunscreen chemicals pose no or low risk to animals or humans.”

For these reasons, the team asked whether UV filters in combination would induce higher toxicity than they do alone and whether these interactions might worsen, becoming increasingly dangerous to animals over time. The team set out to answer these questions by analyzing the surface waters of Shenzhen, China for nine common UV filters.

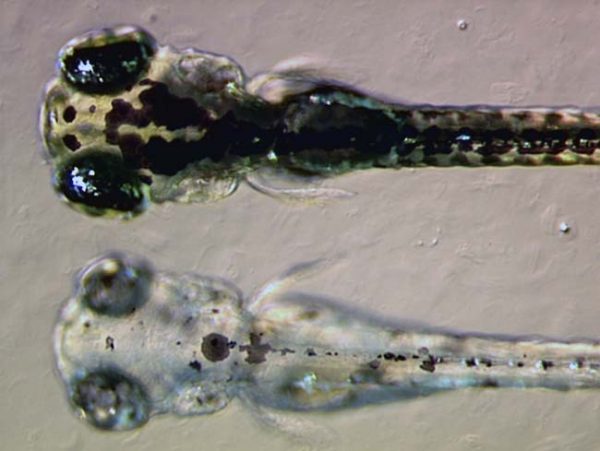

Zebrafish embryos. (Credit: By Adam Amsterdam, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Boston, Massachusetts, United States. [CC BY 2.5 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5) or CC BY 2.5 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5)], via Wikimedia Commons)

The team detected seven of the nine UV filters in the waters near Shenzhen, and not just at the beach; they also found the chemicals in a reservoir and in tap water.

“We did the sampling in two seasons, winter and summer, in order to compare the difference of UV filters occurrence during different seasons,” states Dr. Li. “In both seasons, we collected surface water from 21 locations along the southeast coastline of Shenzhen. The sampling sites covered almost all recreational activities at beaches that were both popular/developed and undeveloped.”

In addition, the team collected water from Shenzhen reservoir, a water source conservation zone, and city tap water.

Searching for answers

“Surface water was stored in pre-cleaned opaque polyethylene bottles at -20 ºC prior to analysis,” comments Dr. Li. “Water was filtered through 0.45 µm membrane before extraction. Water samples were pre-treated by solid phase extraction and analyzed for target UV filters by ultra-high pressure liquid chromatography (UHPLC). We recorded sampling parameters including GPS location, water temperature and pH while doing water collections.”

The researchers then worked on their samples in the lab, where they exposed brine shrimp to the UV filters in the study, both individually and in mixtures. They then fed the exposed brine shrimp to zebrafish, a frequently used model organism.

“Zebrafish adults (aged 3 months), cultured in dechlorinated tap water, were fed Artemia franciscana nauplii twice a day,” remarks Dr. Li. “The Artemia were exposed to different treatments of UV filters and then fed to zebrafish adults continuously for 60 days.”

At Day 25 and Day 47, the team released the adult fish for breeding (2:2, females: males). Next, the researchers examined all embryos produced at three stages: at 24 hours the embryos were checked for mortality; at 48 hours for heart rate; and at 72 hours for hatching rate.”

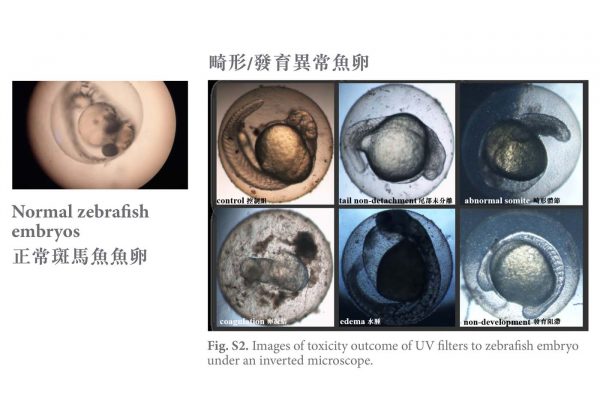

The HKBU study finds the “mixture effect” of UV filters in sunscreens harms the development of fish embryos. The images show the various abnormalities and malformations in zebrafish embryos. (Credit: HKBU, https://cpro.hkbu.edu.hk/en/press_release/detail/91/)

There were no significantly adverse effects for the second generation of exposed zebrafish at either the 24-hour mortality or 72-hour hatching rate checks. However, the 48-hour heart rate check revealed a significant decrease compared to the controls.

“Although the adult fish had no visible problems, their offspring showed abnormalities,” adds Dr. Li. “These outcomes were mostly observed for longer-term exposures (47 days) and elevated levels of the chemicals (higher than what is likely to occur in the environment.)”

The effects of the various UV filters and combinations of these chemicals varied, often in unpredictable ways. This suggests that we will only fully understand how UV filters impact biological systems with further study.

Future research goals

The researchers propose that whether interactions occur or are toxicologically significant depends on several factors, including the endpoints of evaluation, the duration and route of exposure, and the biological target.

“It is worth noting that the three tested UV filters may interact with each other at the environmental level, resulting in reduced toxic effects on embryo development compared with the single compound effects,” clarifies Dr. Li. “For example, after exposure for 47 days, the mortality rate for the environmental-case (EC) mixture showed no difference compared with the control, while that for EC EHMC and EC OC significantly increased.”

Furthermore, the dose itself certainly has an important influence on the results.

“At the level of the worst-case (WC) dose, the adults exposed for 25 days produced embryos with no significantly negative changes in mortality or hatching rate, with the exception of heart rate; however, when the adults were exposed for 47 days, virtually all animals (100%) of the second generation suffered mortality 24 hours after fertilization,” explains Dr. Li. “Any evaluation of the effect of UV filter mixtures, thus, should take both factors of exposure dose and duration into consideration in order to achieve an accurate understanding of the chemical interactions.”

The team hopes to continue their interdisciplinary approach to this research problem, as they found this to be a key factor in their ability to achieve these results.

“The primary techniques we used in this work are chemical analysis by UHPLC and chronic toxic exposure introduced via diet,” details Dr. Li. “We combined chemistry and biology together to better understand the environmental occurrence and toxic properties of UV filters. At the same time, we used some molecular techniques to study the mechanism of enzyme activity when zebrafish embryos are exposed to UV filters. We suggest that multiple research methods should be used to verify a hypothesis at different angles.”

Next in this line of research: a more comprehensive study of how UV filters affect aquatic life.

“Our study clearly shows that UV filters are negatively affecting early life-stage zebrafish,” emphasizes Dr. Li. “Comprehensive evaluation of the complex effects UV filters—and their mixtures—are having on aquatic environments as well as human health, should be undertaken. With the right information, we can take appropriate actions to curtail their potentially harmful effects.”

In the meantime, the team makes it clear that they are not arguing that humans shouldn’t use sunscreen.

“Humans benefit from wearing sunscreen, which protects against sunburn and skin cancer,” remarks Dr. Li. “At the same time, we should consider how those artificial UV filters affect living animals and even human health. UV filters are referred to as endocrine disrupting chemicals. Our study showed that UV filters can be transferred through the food chain (Artemia to zebrafish), and consequently affect early development of zebrafish embryo.”

Top image: Dr. Kevin Leung, leader of the research team. (Credit: HKBU, https://cpro.hkbu.edu.hk/en/press_release/detail/91/)

0 comments