Sustainable Fishing in Alaska: Protecting the Salmon Capital of the World through Research

In the far north, the Alaska Peninsula stretches away from the Last Frontier into the Pacific Ocean. A narrow strip of land dotted with freshwater lakes and intruded upon by ocean inlets–this unique region is intimately connected with the surrounding water.

Nestled halfway down the peninsula’s southern coast are the small villages of Chignik. The area has historically been home to the Aleut people and has been heavily reliant on fishing for centuries.

Home to commercial and subsistence fishing today, Chignik continues to rely upon the salmon returns to the surrounding villages, which are supported by scientists working tirelessly to understand and steward these fish populations.

Beach seining for juvenile sockeye salmon in Chignik Lagoon, Alaska. (Credit: ADF&G staff)

Environmental Research in Alaska

Since 2000, Alaska Department of Fish and Game biologist Heather Finkle has often called Chignik and the surrounding watershed home to her research projects. Now the director of the Kodiak Island Limnology Laboratory, Finkle has deep connections to the area and understands its importance.

“I started working on an ecological assessment out in Chignik back in 2000, and they were concerned, the locals out there, […] they’re concerned about having healthy returns of salmon,” Finkle says.

Finkle’s primary research focuses on the region’s most important fish: sockeye salmon. Unique in their ability to survive in both fresh and saltwater at different stages, understanding the productivity and life history strategies of sockeye salmon has been a priority in the region.

Chignik is located along the southern coast of the Alaska Peninsula, with two lakes, Black Lake at the head of the system and downstream Chignik Lake, connected by the Chignik River. These lakes that connect to the ocean via the Chignik Lagoon provide a prime habitat for salmon to swim upstream to lay their eggs and for their young to be reared in freshwater.

As a result, Finkle and the Alaska Department of Fish and Game have been conducting research on the lakes for many years. A key characteristic of the region is the physical differences between the upper and lower lakes.

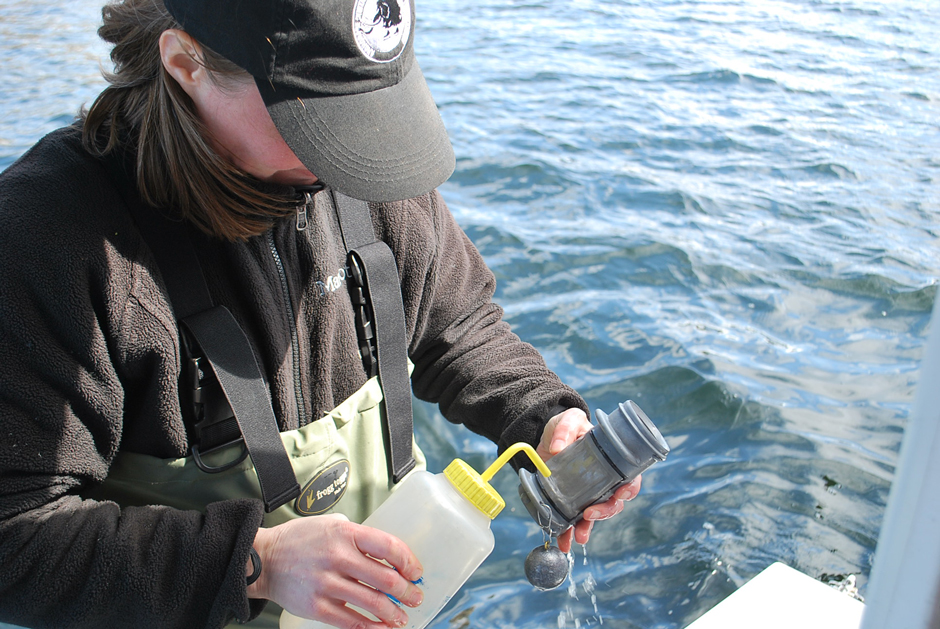

A staff member processing a zooplankton tow. (Credit: ADF&G staff)

The upper lake is a large, shallow body of water that is temperature-sensitive, meaning its ecological conditions can vary widely from year to year. The shallow nature also lends itself to a large aquatic insect population, much different from the common food source of zooplankton that most young salmon feed upon.

Meanwhile, the deeper lower lake offers a distinctly different habitat. Home to more zooplankton and cooler, stable temperatures, juvenile salmon from the upper lake migrate downstream and may interact with lower lake salmon, the extent of which is still being researched.

These genetically distinct stocks of sockeye salmon in each lake have led to Finkle’s main work of understanding what habitat is most suitable for each stock; she appreciates the complexity that these systems pose as she researches salmon life history strategies.

“I think that it’s really important to understand what factors are working and how they work together,” Finkle says. “And that’s the hardest part, is trying to tease out what the drivers are… [but] that’s what I enjoy about it. It’s a puzzle.”

Moreover, Finkle has monitored swings in the salmon populations from year to year, discovering that juvenile sockeye salmon may rear in Chignik Lagoon as well as the lakes and determining that temperature plays a critical role in their survival.

Beach seining for juvenile sockeye salmon in Black Lake, Alaska. (Credit: Heather Finkle, ADF&G)

Connecting Science and Community

After stepping back in 2012 from Chignik to pursue research projects in other parts of western Alaska, Finkle returned to studying salmon in Chignik in 2018. That year and the next few years to follow, the Chignik sockeye salmon fishery experienced some of the lowest returns on record.

In 2020, over $10 million was allocated by the U.S. Secretary of Commerce to address the 2018 fisheries disaster. Subsequently, the state issued a call for proposals for projects to investigate salmon productivity and to parse the causes of the disaster.

“It’s a fishing community, so the economic impact is very apparent. And when the fisheries go down, then there’s a lot of heartache,” Finkle says.

Finkle explains that adult salmon are getting smaller and smaller, and it makes sense that the state known as the “salmon capital of the world” is working to keep population levels healthy.

Behind this crucial statewide industry is the science helping to keep salmon populations healthy. Monitoring habitat, abiotic factors, and population shifts is vital, and using the right equipment drives this progress.

Finkle monitors water quality with a ProSolo and continuously looks for ways to improve her understanding of the ecosystems she studies. Her Fish and Game Kodiak region is one of the only state government departments in the country with an autonomous underwater vehicle, underscoring the importance of their work.

Preparing to launch the autonomous underwater vehicle in Chignik Lake, Alaska (Credit: Kayleigh Frazier / ADF&G)

“We always have the same end goal of trying to maintain sustainable fisheries,” Finkle says.

At the root of Finkle’s research is the understanding that her work is needed to sustain these salmon populations and the livelihood of the communities in and around Chignik. Maintaining healthy salmon populations is critical to supporting the economic and cultural drivers of the villages.

However, local fishermen were already impacted by the damage to fish populations, and it forced some to look to other fisheries or entirely new careers.

“Having a sustainable fishery is really important to a lot of people if you don’t have people in a fishing community, if they leave, then you might also lose dollars,” Finkle says. “[…] If your population declines, then you might lose other services in your town, and that’s the way I think a lot of Alaska [fishing] communities are, [and] what they worry about.”

Conclusion

With only a couple hundred residents and home to many Indigenous peoples in one of the most important salmon fishery locations in the state, the fishery and the town are interconnected. And it is the science behind the work of Finkle and others in the Alaska Department of Fish and Game that helps keep these communities thriving.

“It’s very important for them to maintain their subsistence and traditional lifestyle,” explains Finkle.

She continues, “I want to help them maintain that. I want to make sure that they have those sustainable fisheries and sustainable production to meet their needs.”

0 comments