Sustainable, Sponge-like Material Takes the Color Out of Dyes

Researchers hold a small piece of the sponge-like material in water containing blue dye. After about 10 seconds, the water in the beaker turns clear. (Credit: Mark Stone/University of Washington, https://www.eurekalert.org/multimedia/pub/177125.php?from=401757)

Dyes are part of manufacturing everything from clothing to food all over the world. In fact, every year about 700,000 metric tons of dye change the hue of consumer goods. However, about ten percent of that dye ends up in the world’s waterways, sometimes with toxic results.

Even non-toxic dyes pose a threat in the environment, because changing the color of the water in streams, lakes, holding ponds, and rivers can mean interfering with plants’ ability to photosynthesize. This, in turn, disrupts the rest of the local ecosystem.

“We looked at dyes because they are a major soil pollutant; they are a big deal in the environment,” explains Anthony Dichiara, senior author of the recent research paper and University of Washington School of Environmental and Forest Sciences assistant professor of bioresource science and engineering. “The big problem is that even a small amount of dye can change the color of a large amount of water, and when you change the color you change the light absorption capabilities of that water. Any kind of plants or animals that are living there cannot use that light as efficiently as before.”

Making something useful from waste—sustainably

Dr. Dichiara and the team began this work by exploring new ways to use a familiar material.

“In my lab, we are interested in making new nanomaterials from biomass, and we currently have a project making a new type of paper, so we were really working a lot with wood pulp,” details Dichiara. “At that time we were wondering what else we could do with wood pulp other than paper.”

Working with Chinese visiting scholar Jin Gu, the first author on the paper, the team discussed the possibility of making cellulose fibers at the nanoscale from wood pulp.

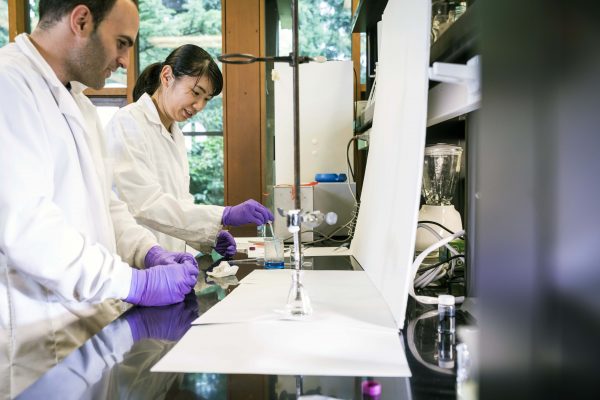

Anthony Dichiara, left, and Jin Gu prepare an experiment to remove color from water using a sustainably made, reusable sponge material. (Credit: Mark Stone/University of Washington, https://www.washington.edu/news/2018/08/01/harmful-dyes-in-lakes-rivers-can-become-colorless-with-new-sponge-like-material/)

“We created a simple chemical process in which you use an oxidation agent to oxidize the wood pulp,” Dr. Dichiara describes. “Then all you need to do is put that slurry into a kitchen blender—literally the kitchen blender that you have in your home, that works—and you make nano cellulose.”

As the team examined the material more closely, they realized that at the nanoscale, the material has a great deal of surface area available compared to the whole volume—and therefore a lot of potential for interaction with the surrounding environment.

“We thought we could use that as an advantage for catalytic applications,” comments Dr. Dichiara. “One of them was water remediation because we do a water treatment using absorption in our lab. We wanted to use a chemical reaction to change the pollutants so they wouldn’t be pollutants anymore.”

The team settled on dyes as a good target to test their materials, since large volumes of water can be polluted by small amounts of dye. However, the team aimed to simply turn the dyes clear instead of removing them from the water, allowing plants to photosynthesize normally again. Reducing agents can chemically change the structure of dyes until they are clear, but it is an inefficient and slow process.

Therefore, the team developed a sponge-like material with their nano-cellulose and added a catalyst to speed up that reaction. Adding tiny particles of metal to the sponge to impart catalytic qualities to the material proved to be challenging based on their goals.

“We were trying to find a way to make the dye colorless, and one way to do it is to use a catalyst,” states Dr. Dichiara. “The catalysts are basically metal particles, but now we were facing a new challenge because we had just made that new, very fancy, nano cellulose from wood pulp, a sustainable material; and now we had to synthesize or add metal particles to it. In other words, if we added that metal particle, it was no longer going to be a sustainable material because the process to make the metal is not sustainable.”

University of Washington researchers created a sponge-like material, left, from wood pulp and small bits of metal that can remove color from dyes in water within seconds. More of the material is shown in the tubes on the right. (Credit: Mark Stone/University of Washington, https://www.eurekalert.org/multimedia/pub/177123.php?from=401757)

It takes various chemicals to make these catalytic metals, and many are very toxic, such as reducing agents and surfactants.

“We were disappointed, because we were challenged to make the nano cellulose, a green material, and we didn’t want to pollute it with metal,” remarks Dr. Dichiara. “Luckily, we found a way to actually introduce the metal on the surface of the fibers without using any reagents at all; we simply mixed the salt containing the metal with the material, heated it at 80 degrees for one or two hours, and the reaction takes place without anything else. The metal segregates onto the surface of the fibers and creates the catalyst. For us, it was exciting because we found a way to make a truly green catalyst.”

Applications for the sustainable “sponge”

The final product the team created is a sponge that is over 99 percent air, embedded with catalyst particles to remove color, and filled with large pores to enable easy water flow. It resembles a standard household sponge in that it can be used again and again, once the water is squeezed out of it.

More importantly, the sponge is fast and effective. Pouring colored water through it, clear water passes out the other side of the sponge. It only took the sponge about 10 seconds of swirling inside a container of dyed water to remove all of the color. The researchers envision the sponge being used to “drag” a lake to remove dye colors from it, but this is just one example of an application for the material.

“It could catalyze any type of reaction where you need some sort of green reducing agent,” explains Dr. Dichiara. “On a broader scope, if you changed the type of metal that you put on the surface, you could also adjust the different range of chemistry that you could do. Right now it works well with palladium. We also tried with silver, because although silver is not necessarily a good catalyst, it has other properties, such as anti-microbial properties.”

The practicality of using some metals will really depend on cost as it relates to the potential applications.

“Palladium will catalyze certain reactions that, say, nickel won’t, at least not with the same efficiency, and only after tweaking the process a little bit,” adds Dr. Dichiara. “We definitely don’t want to add any toxic chemicals for the synthesis of the catalyst.”

Researchers hold a small piece of the sponge-like material in water containing blue dye. After about 10 seconds, the water in the beaker turns clear. (Credit: Mark Stone/University of Washington, https://www.washington.edu/news/2018/08/01/harmful-dyes-in-lakes-rivers-can-become-colorless-with-new-sponge-like-material/.)

This material might someday be able to work as part of existing water treatment systems, but it works very differently from conventional treatments.

“Usually when you’re treating to a drinking water standard, you want to remove the different pollutants from the water; this process does not remove the molecules,” clarifies Dr. Dichiara. “It just changes its structure so that it no longer absorbs the light at the same wavelength. So it’s still there, it’s just a different molecule. That new molecule might be as toxic as the previous one; it might be less toxic.”

For example, the team used Congo red dye to test the material.

“We believe that the toxicity of Congo red is caused by the benzene rings that are present on the molecule’s structure,” details Dr. Dichiara. “We know that after the catalytic reaction those benzene rings are still present, they were not changed whatsoever by the catalyst. It’s not this part of the molecule that is changed, so it’s very likely that this molecule is still toxic. So I wouldn’t want to drink that water, but at least the water is clear so the plants can still use the light for photosynthesis.”

Furthermore, if there is a specific difficulty in treating water for a particular molecule using conventional processes, this catalytic reaction material can change that molecule into another molecule that is easier to treat.

“Sometimes you have too much pollution,” remarks Dr. Dichiara. “Sometimes you want to control the algae or the microbial population in certain environments. These materials provide the flexibility to deal with different possible treatments very efficiently, which is pretty interesting, because most of these molecules are pretty big, and it typically takes a lot of time to change them. So the fact that we can do it within a matter of seconds—that tells you a lot, it’s pretty efficient.”

[youtube id=”a70IvqljlS0” width=”620″ height=”360″]

Video: Researchers hold a small piece of the sponge-like material in water containing blue dye. After about 10 seconds, the water in the beaker turns clear. The sustainably made sponge material can be reused multiple times. (Credit: Kiyomi Taguchi/University of Washington, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a70IvqljlS0)

0 comments