Swirling Eddies In Open Atlantic Ocean Carry Low-Oxygen Dead Zones

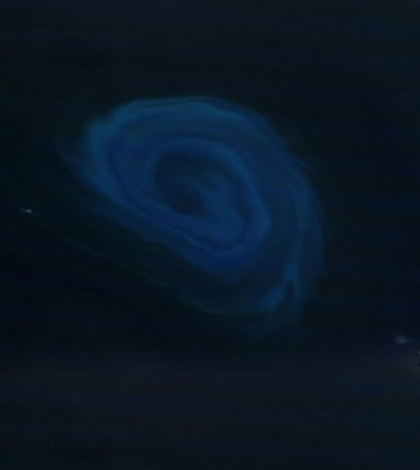

An ocean eddy as viewed from a satellite. (Credit: NASA Earth Observatory)

Off the coast of West Africa, German and Canadian scientists conducting a routine monitoring project found something entirely unexpected amid the swirling waters of Atlantic eddies: Nearly anoxic dead zones containing the lowest oxygen levels ever recorded in the open Atlantic. Their findings were published online in the open-access journal Biogeosciences.

The unique geography and morphology of West Africa give the region an important role in the interaction between atmosphere and ocean. Existing research has established links between Saharan dust and oceanic circulation and productivity, but there’s plenty more to be uncovered through “more concerted study,” says Douglas Wallace, co-author of the recent paper and professor at Dalhousie University’s Oceanography Department.

“There was a lack of data from the region,” Wallace wrote in an email. “Together with scientists from the small island state of Cape Verde, we decided to establish long-term measurements, including an ocean mooring that included an oxygen sensor as well as some trial deployments with special profiling floats.”

Alongside that effort, Wallace helped scientists from the Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research in Kiel, Germany, establish a research project to learn more about tropical oxygen minimum zones, areas of low oxygen in the ocean that can have major impacts on global biodiversity, nutrient and carbon dioxide cycles. Between both projects, the researchers found the low-oxygen zones they were seeking, but with characteristics they did not anticipate.

Using a combination of moored sensors, robotic floats, gliders and satellite data, the researchers found that churning eddies were producing dead zones with record-low oxygen levels at remarkably shallow depths in the Atlantic Ocean. In fact, Wallace said he had initially thought deploying oxygen sensors at depths as low as 40 meters was a mistake. His reaction when he was proven wrong?

“Very, very surprised,” he wrote. “I could not have imagined that the waters at such shallow depths in this region could approach anoxia. No one expected this and nothing like this had been observed before.”

The dead zones recorded by the researchers represent extreme ocean habitats, with oxygen concentrations ranging from nearly anoxic to no higher than 0.3 milliliters of oxygen per liter of seawater, or about 100 times lower than oxygen levels outside the eddies.

Ocean currents carry the eddies slowly westward. Upon encountering a reef or island, the dead zones within can cause mass fish kills. And the researchers noticed that even zooplankton, tiny animals that only come to the surface at night to feed, remained at the surface all day to avoid the dead zones below.

Wallace says the Helmholtz Centre continues to study the eddies today. Many researchers involved in the study plan to discuss their findings at a symposium in Cape Verde in June, and will determine what future studies in the region might entail.

Wallace noted that the study’s results highlight several things, like the importance of new technologies, cooperation with local scientists and the potential for using ocean eddies as natural laboratories in the future.

But the key takeaway is a bit broader. “The ocean is full of surprises,” wrote Wallace. “And not only the deep ocean.”

Top image: An ocean eddy as viewed from a satellite. (Credit: NASA Earth Observatory)

0 comments