Texting Buoys Helping to Create a Data Democracy

The Cleveland Lake Erie buoy measures weather, waves, and water quality to support environmental studies, including a proposed offshore wind energy project. (Credit: Ed Verhamme/Limnotech, https://www.limno.com/environmental-data-buoys/.)

Over the summer, the Great Lakes Observing System (GLOS), which is dedicated in part to sharing buoy data with the public, got a viral social media boost to their text-a-buoy system. The GLOS texting buoys provide information about water and weather on the Great Lakes for anglers, boaters, and anyone else who wants it, including live video feeds from some buoys. GLOS communications manager Kristin Schrader spoke to EM about why the texting buoys are getting their 15 minutes of fame now—and the benefits these trusty texting sentinels of the lakes offer to humans.

Texting buoys

“This feature was designed by our contractor, LimnoTech, to provide a low-tech way for people to get info from the buoys,” explains Schrader. “Even though there is a lot more information available through glbuoys.glos.us, it didn’t exist in the mobile-optimized, phone-friendly format in which it resides today. So if you didn’t have a smartphone, or you found the data hard to look at on your mobile this was a good interim step.”

The buoys have had texting capacity since about 2014, but they weren’t deployed specifically with this in mind.

“The texting was just a way to fill in for people who didn’t have browser access, nobody thought of it as a replacement,” remarks Schrader. “We did have people using the service, though, since the beginning.”

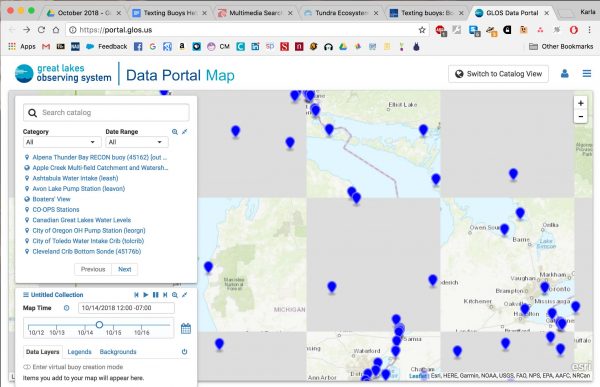

GLOS data portal map, Sun Oct 14. (Credit: Screenshot.)

Over the summer, thanks in part to social media, the buoys got an unusual amount of attention—and that translated into thousands of texts instead of hundreds. The GLOS team was excited by the development and got an additional line for their busy buoys.

“Right now it is the novelty, but we are looking forward to seeing if there is a sustained rise in usage,” details Schrader. “Without ongoing data there really isn’t a way to tell if this is a blip or an additional way that people will interact with the lakes. Citizens of the basin have real ownership of the resource, whether they live on the water or not. It’s possible that a meaningful number of people will continue to check in, just like they ping for weather or news updates.”

The buoys can text information that has many applications, and can even save lives on the water. Researchers and local officials also use the buoy data to manage drinking water systems, identify potential risks to recreational users, and augment research data.

“These buoys are all environmental observation buoys,” Schrader describes. “They capture data and share it in real and near real time. Depending on the buoy it can capture things like wind speed or wave height. Some have thermistors beneath that give detailed temperature readings at several levels below the water. Buoys in western Lake Erie can capture information like chlorophyll or dissolved oxygen to help keep an eye on algal blooms and hypoxia.”

Deploying the St. Joseph, Lake Michigan buoy, which monitors wind speed and direction, air and water temperature, relative humidity, and wave direction, height and period data. (Credit: Ed Verhamme/Limnotech, https://www.limno.com/environmental-data-buoys/.)

Creating a data democracy

Although GLOS manages the buoy data, they don’t control the buoys, which are all owned by different entities.

“A lot of people think that buoys are deployed by the government, and some are; the NOAA Great Lakes Environmental Research Lab has quite a few buoys deployed,” comments Schrader. “But they are not the only game by a long shot. There are buoys operated by research institutions, universities who need specific data to support their research, and there are also buoys deployed by private industry. The Cook Nuclear Plant shares data from its buoy, and water treatment facilities, for instance Cleveland Water, share theirs. GLOS doesn’t own any buoys at all; we are here to manage the data and make it easier to discover and use.”

Right now, most Great Lakes buoys come out of the water in the winter. They just aren’t designed to deal with ice, and buoy operators take the downtime, which comes with the colder weather, to clean and repair the buoys, and to calibrate sensors. However, this causes an interruption in buoy data—one that Schrader and others hope that cabling underwater buoys to the bottom of the lakes might eventually solve.

“Taking the buoys out from time to time is important for maintenance, but ours leave the water in October and don’t usually go back in until May,” states Schrader. “That is a lot of time that is ‘dark’ as far as data goes.”

The South Haven Lake Michigan buoy provides real-time weather and wave data for boaters, anglers, tourism businesses, weather forecasters, and others. (Credit: Ed Verhamme/Limnotech, https://www.limno.com/environmental-data-buoys/.)

During those “dark” months, there are still boaters on the water, ships transporting cargo, and of course, wildlife. In short, it doesn’t make sense to Schrader that there aren’t year-round sensors helping us understand what happens in the Great Lakes when it is cold.

“There is a system in Canada, in the northwest, called Neptune, and it is a good example of what we will eventually get to in the Great Lakes, I hope,” adds Schrader. “Fiber optic cables lie on the lake floor and essentially wire the area to transmit information. You can attach sensors and cameras, and test things like oxygen, temperature and velocity, for instance. It would be fantastic to have that information constantly, and when the surface instruments are in it would amplify the data gathering even further. We use the lakes too heavily not to know what’s happening.”

For Schrader, the many ways this buoy data is used is the most important part of this story.

“All of this data, generated from so many places in pursuit of so many things, has everyday applications,” emphasizes Schrader. “People who run fishing charters use the thermistor info, people who go boating check the wave heights before they drive to the coast so they don’t waste their time and gas going to the boat when the water is too rough. Municipalities with waterfronts can look at information to help them assess improvements, and beach managers can look at conditions to decide whether or not swimming is safe.”

Live image from buoy Cleveland Wind 45169 taken at 1410 EDT Sun Oct 14. (Credit: Screenshot)

Moreover, there are probably many potential applications for this data that aren’t being exploited yet.

“We have been participating in hackathons, like the one run by Cleveland Water Alliance,” says Schrader. “People who participate in those are driving technology back towards the water. Coming up with new ways to gather data, less expensive tools and neat ways to visualize what we receive. It’s a symbiotic relationship.”

The combination of different data buoys monitoring various parameters while sharing the data for public access is creating what Schrader calls a “data democracy.”

“Everyone has access to this data: you, me, a third-grade classroom, the City of Chicago, and a homeowner near the Apostle Islands,” states Schrader. “You might not have a fancy lab, but you can find and consume this data at your leisure, at no cost other than we’re a small government program serving it. So an applications developer can use this data to invent something that makes it more productive for a fisherman, whose kid uses data for the science fair, and then grows up to be in the Coast Guard.”

By making the buoy data available to everyone, all of the time, the GLOS helps puts all of those users on equal footing.

“The same quality data is served to everyone who wants to use it, and there’s no limit to what one can do with it,” concludes Schrader. “The Great Lakes are big and complicated, and we work them so hard that there is a huge, diverse group of people who need data to make informed decisions, and with these buoys and the portals through which their data are consumed, we all get equal access to the tools.”

Top image: The Cleveland Lake Erie buoy measures weather, waves, and water quality to support environmental studies, including a proposed offshore wind energy project. (Credit: Ed Verhamme/Limnotech, https://www.limno.com/environmental-data-buoys)

0 comments