The Center for Coastal Studies: Dedicated To Monitoring the Health of Cape Cod and Nantucket Waters

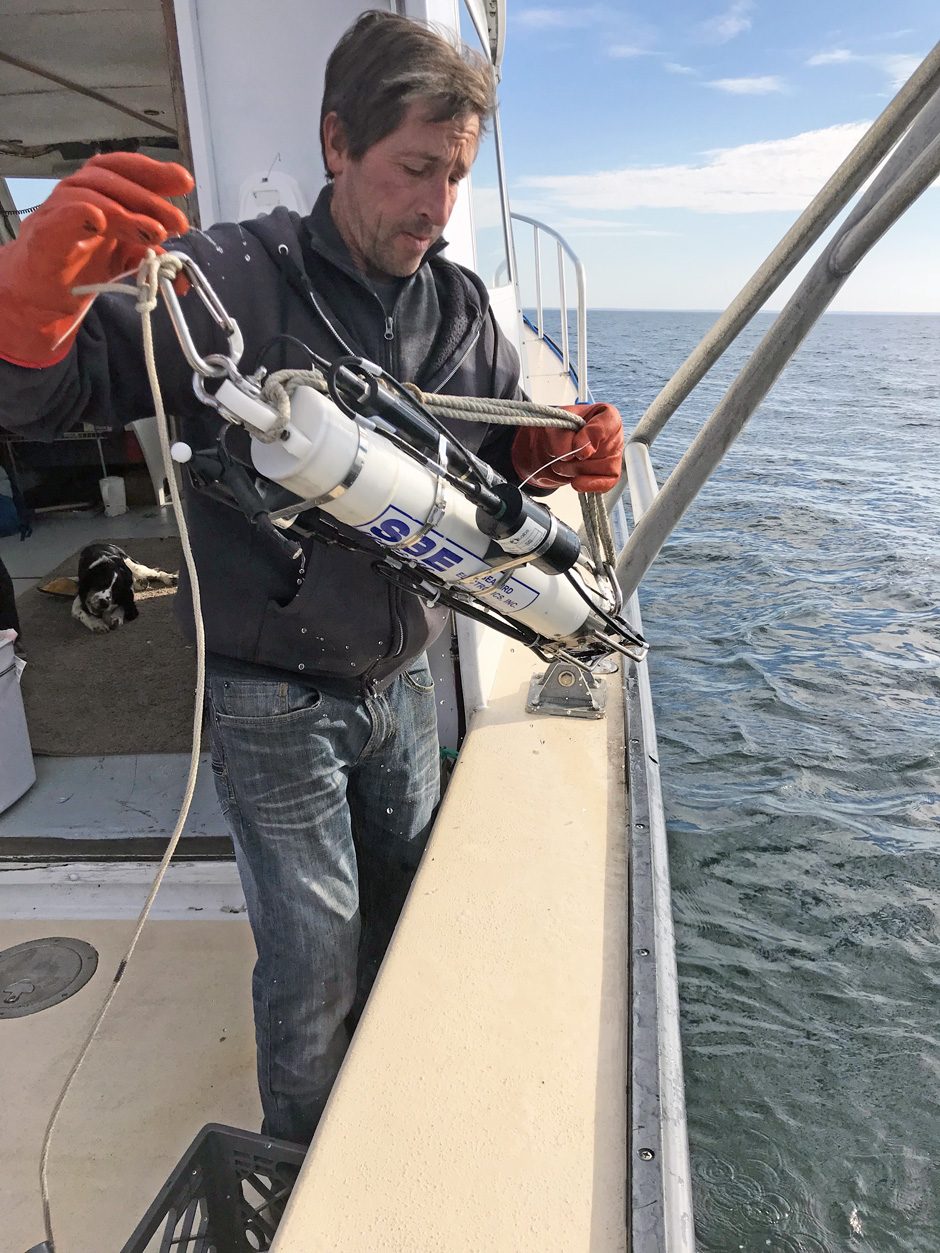

Marc Costa (CCS captain and director of field operations for the monitoring program) deploying the Seabird CTD. (Photo Credit: Center for Coastal Studies)

Marc Costa (CCS captain and director of field operations for the monitoring program) deploying the Seabird CTD. (Photo Credit: Center for Coastal Studies)The central mission of the Center for Coastal Studies emphasizes scientific research on marine mammals of the western North Atlantic as well as the coastal and marine habitats and resources of the Gulf of Maine. The Center also seeks to promote stewardship of coastal and marine ecosystems and provide educational resources that encourage responsible use and conservation of coastal and marine ecosystems. It also seeks to collaborate with other institutions and individuals to advance its mission.

Dr. Amy Costa, Director of Water Quality Monitoring Program and Associate Scientist at the Center for Coastal Studies, leads the water monitoring effort as part of the overall mission of the Center. “We have 100 to 120 stations, with 12 stations in Cape Cod Bay and 10 stations in Nantucket Sound,” Costa says. “We collect many types of water quality data, including temperature, salinity, dissolved oxygen, turbidity, chlorophyll-a, and nutrients (nitrogen, phosphorus, silicate).”

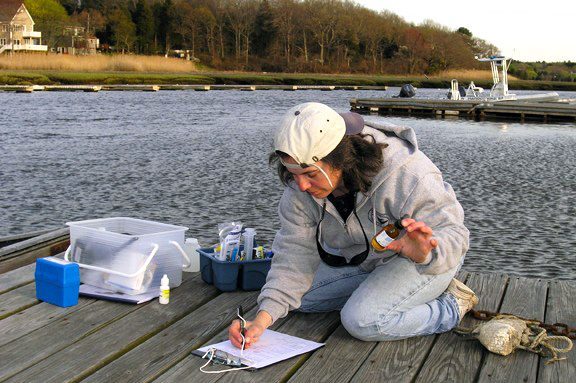

Field equipment primarily consists of YSI Handheld ProDSS units or Pro Plus units, the ProDSS units being more advanced and having optical oxygen sensors rather than the membrane covered sensors of the Pro Plus. A Seabird SBE 19plus V2 SeaCAT profiler CTD is used for the deeper stations to measure temperature, conductivity, depth, dissolved oxygen, and fluorescence. Field data and samples are gathered by volunteers and staff in the May to October timeframe each year. Most water samples are collected weekly, or bi-weekly during these months, but the offshore stations in Cape Cod Bay are monitored monthly, year round. There are about 20-25 volunteers that help gather samples for the Center. Most of the volunteers are retired. Some are former scientists; others are members of the public from a variety of backgrounds. “We started our volunteer program 14 years ago, and we’ve had steady participation since then,” says Costa. Volunteers are equipped with field supplies to measure environmental parameters such as Lamotte kits to measure dissolved oxygen and refractometers to measure salinity. They also collect water samples which are taken back to the Center’s lab to be analyzed for nutrients, turbidity and chlorophyll.

Carol Carson, a volunteer, samples in the Jones River. (Photo Credit: Center for Coastal Studies)

In the Center’s lab, an Astoria Pacific autoanalyzer is used to measure nutrients. It has four separate channels to simultaneously measure silicate, ammonium, nitrate+nitrite, and ortho-phosphate using micro-segmented flow analysis. The lab has a Lachat QuikChem Flow Injection Analysis System that is also used to measure nutrients and anions, and a CE Elantech elemental analyzer which is used to measure particulate organic nitrogen (PON) and particulate organic carbon (POC). A Turner Trilogy fluorometer is used to measure chlorophyll.

Costa’s lab coordinates sample collection and performs all chemical analyses. They also work with other research organizations such as Waquoit Bay, whose National Estuarine Research Reserve (NERR) was featured in a previous Environmental Monitor article.

The Center’s lab also works with other research groups, environmentalists and towns to monitor Cape Cod Bay and Nantucket Sound health. “We collaborate with several towns on the Cape including Harwich, Barnstable, and Falmouth to help collect samples,” says Costa. “Our goal is to not only gather the data but also have it available online for anyone who wants to utilize it.” The data is available for download in graphical or tabular form through a link on the Center’s website.

Costa has been the Director of this program for 14 years. In that time, data have varied considerably due in part to the area’s dynamic weather events. “We have had drought years and very wet years,” recalls Costa.

(left) Turner fluorometer (under the hood) and CHN analyzer. (right) Astoria Pacific autoanalyzer and Lachat QuikChem Flow Injection Analysis System instruments. (Photo Credit: Center for Coastal Studies)

Currently, Cape Cod is trying to address nitrogen in its estuaries. “About 80 percent of the controllable nitrogen that enters the Cape’s watersheds is from septic systems. This nitrogen pollutes the estuaries, leading to degraded water quality, and in severe cases, can lead to Harmful Algal Bloom (HAB) events and fish kills,” Costa notes. “We’re definitely seeing more degraded areas than we did in the 1950s as the population has increased. In the 1950s, there were fewer than 50,000 people. By 2010, there were more than 200,000 people.” The population also varies a great deal seasonally, due to Cape Cod’s continuing popularity as a summer destination. “The population can increase by threefold or more in the summer months,” adds Costa.

Costa has had a lifelong interest in the Cape Cod area as well. Her doctoral research was completed at the University of Rhode Island, Graduate School of Oceanography, where she researched zooplankton aggregations and their relationship to the foraging behavior of right whales in Cape Cod Bay. “Doing the research made it clear how important water quality is,” Costa recalls. “Before this program started in 2006, there were no long-term water quality programs that encompassed the entire Cape. We set out to change that. Since then, we have been gathering baseline data all over the Cape.” While the lab looks for emerging trends, despite having over a decade of data, the timeline is too short to look at global warming trends given the inherent variability in the data.

Amy Costa, associate scientist at the center, using the fluorometer. (Photo Credit: Center for Coastal Studies)

While it may seem like there isn’t much a single person can do to help the water quality of Cape Cod or other areas, in the face of large forces such as tripling population growth and severe weather events, Costa indicates there are some things residents can do to help improve the water. “People can limit their use of fertilizer. They can also use native plants, pick up after their pets, not dump in the waterways and support town efforts in wastewater planning,” she emphasizes.

Costa notes that Cape Cod is especially vulnerable to nitrogen inputs to the groundwater from sources such as septic systems or fertilizer. “Cape Cod has sandy soil, so nitrogen-enriched groundwater leeches right through, moving quickly towards our estuaries.”

0 comments