The East Bank Die-Off: A Coral Reef Whodunnit

Dr. Davies back on land. (Credit: via Dr. Sarah Davies, Boston University)

Dr. Davies back on land. (Credit: via Dr. Sarah Davies, Boston University)In July of 2016, several divers visiting the Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary and its coral reefs off the coast of Louisiana and Texas discovered that coral was dying. However, there was also a clear line in the reef. Below it, things were dead, and above it, creatures were surviving.

Researchers like Sarah Davies, who had worked on that specific reef since about 2007, wanted to find out what was causing the die-off.

“We had that die-off event happen in 2016, and it was totally anomalous,” explains Dr. Davies, assistant professor of biology at Boston University. “I actually hadn’t been working out there for a few years because I did my post-doctoral work on reefs in Belize and Panama, but the sanctuary people called me and asked if I wanted to come out and sample, and of course I wanted to get back out there.”

Dr. Davies had already been working on questions surrounding how events that take place on land can influence events in the water—even 100 miles offshore. The question was, what specific set of conditions would cause this unusual die-off pattern?

(left) Dr. Davies and an unexpected “volunteer” (top right) Dr. Davies (bottom right) Dr. Davies working in the water. (Credit: via Dr. Sarah Davies, Boston University)

Eventually, Dr. Davies and the research team proposed a link between the die-off spotted in July and the Tax Day floods which took place three months earlier in April of 2016—a flood event that was unusual.

“That’s what was unique about the Tax Day floods: they were just rainstorms,” states Dr. Davies. “They weren’t hurricanes. They weren’t causing mixing in the Gulf of Mexico. I think it was really just the sheer amount of freshwater that caused stratification and an associated algal bloom that then led to low amounts of dissolved oxygen that in turn led to all the bad stuff downstream.”

In other words, too much rain alone, such as that caused by a hurricane, isn’t enough to trigger this kind of die-off.

“When Hurricane Harvey hit and they were making projections about the amount of fresh water, we were thinking, ‘Oh no, this could really happen again,’” details Dr. Davies. “But it turns out we didn’t really understand what environmental parameters are required to induce hypoxia, and it definitely can’t really happen during a hurricane, because you get massive ocean mixing.”

Solving the mystery

The team got to work on why the Tax Day floods were different.

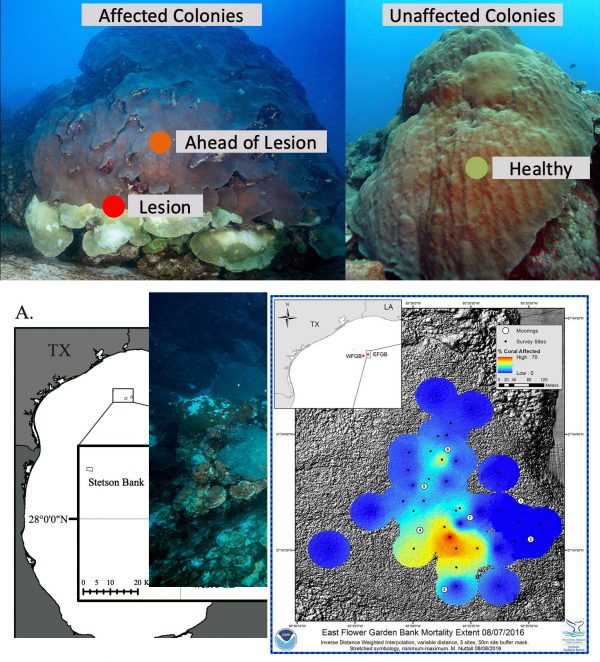

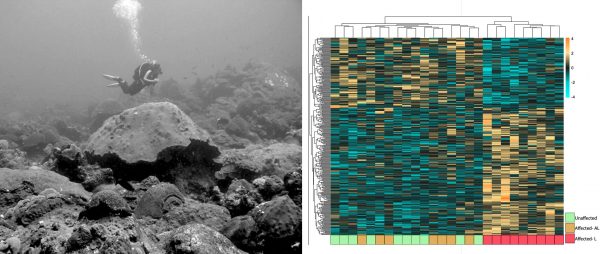

“We sampled the coral colonies along the lesion line—the place where that line of death was in the photos—and then we sampled a healthy part of the same colony and healthy colonies on the same reef,” comments Dr. Davies. “Then we looked at their gene expression. We saw that a lot of corals were dead, but not every one of them was dead, and not every part of every colony was dead. There was definitely a depth gradient, a line above which everything seemed to be okay.”

(top) Before and after die-off images of coral, Orbicella faveolata and Orbicella franksi (bottom) Diagram of die-off locations. (Credit: via Dr. Sarah Davies, Boston University)

Naturally, Dr. Davies was curious about what was happening right at that threshold, versus a healthy region within the same colony.

“Corals are clonal, so you have the same genetic material throughout the whole individual, and there are many clonal polyps that are all the same thing—but they can be acting very differently,” Dr. Davies says. “You can control for genetic background and place corals under different conditions in the lab, and in this case, it was just in a different condition in the wild.”

The team found signs of hypoxia, and after investigating gene expression, found evidence that corroborates their prediction that it was a low dissolved oxygen (DO) scenario that triggered the die-off.

“We’ll never know because we weren’t out there in that moment,” adds Dr. Davies. “It takes a while to get a fleet of researchers on a ship and get them offshore. By the time we got there, unfortunately, a lot of the active part of the die-off had disappeared.”

Dr. Davies is now focusing on the composition of the “perfect storm” of conditions that might contribute to this kind of die-off.

“I think you need a lot of rain,” explains Dr. Davies. “You need warm temperatures, which help to stratify the water column, and then you need nutrients, and the nutrients should come with the rain. You combine those three things and you’ve got the perfect storm of water column characteristics.”

According to Dr. Davies, a combination of changes in ocean circulation increasing freshwater in some areas, and droughts in other areas are causing stratification in multiple places. Warming freshwater on top causes algal blooms, especially when runoff that is high in nutrients enters the ocean. All of these factors will cause these low DO events on reefs to become more and more common.

(left) Diving after the die-off (right) Comparison of affected and unaffected colonies (Credit: via Dr. Sarah Davies, Boston University)

“There is also probably variation within a species,” clarifies Dr. Davies. “Certain individuals will be more or less able to deal with low oxygen. Intertidal organisms, for example, hunker down on the rocks and sit there until the water comes back up. There are behaviors and physiological traits that can help when DO is low, and that probably varies, both by species and within a species. So I think we have no idea how different species are going to respond. I’m really interested in trying to see if there is variation among corals, and who can deal with lower DO environments and why.”

A future of die-offs?

In the past several years, massive storms with less wind and more rain have become more common—and this is a trend we are likely to see continue. This doesn’t bode well for coral.

“I think that’s the key: if we get more rain and less wind, less wind will mean less mixing, and then we risk those stratification events happening,” remarks Dr. Davies. “I think that’s a real worry. I don’t think we have good predictive powers for where these events will happen. I never thought something that would happen in Houston would really cause water stratification out all the way to 100 miles offshore, and the reefs are really deep there, too.”

That’s a point worth highlighting: The reef cap is at about 65 feet, making it a deeper reef. Yet the effects of the Tax Day floods weren’t buffered by the distance from shore or the depth.

“As long as you have sunlight, the die-off should be a little bit buffered, because the symbiont should be providing oxygen to feed the coral’s respiration,” details Dr. Davies. “This complex interaction might make corals more resilient. I don’t know, but it’s definitely something we’re thinking about working on in the future.”

The team is making use of its unique interdisciplinary composition, which affords it an unusually broad and deep bench of expertise.

The research team together. (Credit: via Dr. Sarah Davies, Boston University)

“A big group of us has a collaborative grant through the National Science Foundation to investigate the effects of these big freshwater events on reefs, and it’s a really diverse team,” states Dr. Davies. “We’ve got ocean chemists and bacterial genomicists (both from Texas A&M) that are looking at water column characteristics. Adrienne Correa (Rice University) is looking at the die-off process from the bacterial and viral standpoint, and I’m approaching it from the coral and algal symbiont point of view. We also have a sponge researcher (University of Houston) because we think that, for whatever reason, sponges are the first to die during these low DO events. Their death facilitates more and more bacteria growing, and their growth, in turn, pulls down more oxygen, so it creates a kind of feedback loop.”

A diverse group of researchers working together to answer complex problems has its own, obvious appeal, but Dr. Davies also sees this as part of a larger trend in science.

“I only know stuff about corals, gene expression and physiology, so I’m learning a lot about physical oceanography and chemical oceanography,” comments Dr. Davies. “There are these entire fields I know literally nothing about. Working together is a great way to piece together the puzzle in a much more robust manner than just a single person trying to figure out what the coral is doing. And it’s fun too. Otherwise, you’re just in your little echo chamber like, ‘Let me tell you about this coral.’”

0 comments