Toxic Potential: Oil and Gas Wastewater on Roads

A water truck sprays down a dusty road on a construction site. (Credit: By Smurrayinchester [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], from Wikimedia Commons)

A conflict has been unfolding in Pennsylvania recently—one that has implications for the many people living near the more than 1.3 million miles of unpaved road across the country. According to the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), unpaved roads made up about 35 percent of the over 4 million miles of American roads in 2012. Those roads and the dust they inject into the air are a serious problem, so dust suppression techniques across the country vary based on what’s available, affordable, and effective.

Up until recently, conventional Pennsylvania oil and gas drilling wastewater (OGW) has been used to suppress dust on unpaved roads and deice others. However, in May of this year, the Pennsylvania Environmental Hearings Board limited the use of OGW brines on unpaved roads in the state. Now, as that decision is reviewed by the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (DEP), recent research in the American Chemical Society journal of Environmental Science and Technology has demonstrated the toxic potential of conventional OGW on unpaved roads.

When “beneficial reuse” isn’t beneficial

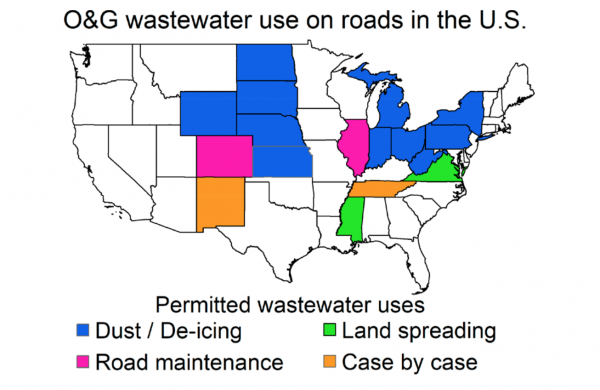

Since 1988, conventional oil/gas drilling wastewater is permitted as “beneficial reuse” when used as road brine. Whether suppressing dust on unpaved roads or deicing paved roads, OGW was repeatedly applied to many roads in the state until 2016 when its use as a brine was questioned. Especially in northwestern Pennsylvania, where this kind of application was common—as it is in at least 13 states.

OGW as a road brine reduces dust emissions, helping to lessen the incidence of dust-related respiratory and cardiovascular diseases. It’s also cheap or free compared to the commercial brine which typically costs around $0.25/liter ($0.95/gallon).

Unfortunately, road brine can leach into groundwater, surface waters, and soil, bringing whatever contaminants it contains with it. A recent study conducted by Penn State, University of Alberta, and INDIGO Biosciences researchers found that spreading OGW as road brine contributes high levels of radium into the environment.

“The environmental hearings board in Pennsylvania just ruled on a case that was brought forward by a private citizen in Warren County who was challenging the DEP’s spreading of oil and gas wastewater on roads on a number of fronts,” Dr. William D. Burgos,a professor in the Pennsylvania State University’s Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, one of the study’s authors. “One front was that the environmental hearings board ruled on was that the original decision by the DEP to allow these materials to be spread was in error. It was literally during our press embargo that this other case was decided.”

These states all allow oil and gas wastewater as road spreading. (Credit: Tasker, et al https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.est.8b00716)

Burgos and the team began their investigation four years ago, without any intent to study applications with OGW—in part because they had never heard of it before investigating the impacts of centralized waste treatment plants.

“We started investigating these plants because we believed they would have a critical environmental impact because they serve a region,” details Dr. Burgos. “So all of these tanker trucks filled with wastewater arrive at these treatment facilities, and are then processed as a single point source discharge.”

Deep dives into data from the Pennsylvania DEP and the Pennsylvania Bureau of Oil and Gas revealed exactly how much produced water came out of each well and where it went. Requirements for oil and gas well operators require that they file reports regularly, detailing what happens to wastewater from conventional drilling.

“It’s basically a list of disposal options, one of which is a centralized waste treatment plant,” Dr. Burgos describes. “So we were able to use that kind of information to figure out where the majority of the wastewater was going to the plants, and then focus on those plants that had relatively high flow compared to the stream flow at that point. Where it would be a minimum amount of dilution occurring and then assess the aquatic health and sediment health in those environments. But during that process, we found another category that was in this report that the operators can submit called ‘road spreading,’ and that seemed like a really curious disposal option.”

From there, the team went to work determining what “road spreading” was and how spraying OGW on the road was an approved disposal method for conventional wells.

“We didn’t know exactly what it meant in the beginning; we didn’t even think it was real,” adds Dr. Burgos.

Most significant source of radium in the environment

Once you get past the shock that oil and gas wastewater from conventional wells had an officially approved “beneficial” use being sprayed on roads, it’s not necessarily a surprise that this happened in Pennsylvania. The state, especially the northwestern region, has a deep history of conventional oil and gas development going back 140 years. The first oil well in the nation was drilled in northwestern Pennsylvania in 1859.

The state is also home to many unpaved roads. Most have high levels of fine clay content, making dust a serious problem.

“Dust is a significant environmental issue in its own right,” Dr. Burgos describes. “Inhaling fine particulates causes problems for people with asthma and causes other sorts of respiratory distress. We just want to make sure that we’re not trading off one environmental problem for another.”

The team set out to determine whether OGW road spreading was harmful.

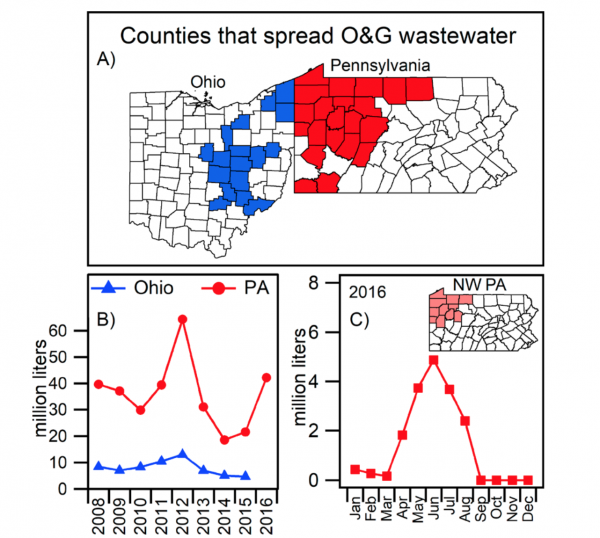

Counties in PA and OH where OGW was sprayed, and volumes of spray dispersed. (Credit: Tasker, et al https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.est.8b00716)

“We wanted to chemically characterize what are in these brines,” comments Dr. Burgos. “Then we went a little bit further and we did some laboratory scale experiments following some standard methods where we applied those brines to a representative road aggregate of northwestern Pennsylvania and then did a simulated rainfall leaching to determine how mobile they were after application.”

After contacting a number of townships and speaking with the roadmasters in those townships, 14 roadmasters came forward and agreed to provide the team with OGW samples.

“When the dust season comes up, which is around here sort of like April to August, the roadmaster will fill his water tank spreader truck and go out and apply it onto roads,” states Dr. Burgos. “But first, the townships have to file a notification with the Pennsylvania DEP to tell them exactly where they’re going to spread, when they’re going to spread it, and roughly how much volume they think they’re going to spread on that particular stretch of road.”

When a roadmaster first asks the DEP for permission to spread OGW on the roads, they must file a certificate of analysis. These certificates of analysis have a set number of analytes required by the DEP listed on them, but that list of analytes never includes radium.

“The certificates of analyses are on file, and we were able through an FOIA request to obtain 53 between the state of Pennsylvania and the state of New York,” explains Dr. Burgos. “Each one represents the initial request because after describing the analytes once, they basically say chemical composition as previously determined.”

After collecting samples and conducting statistical analyses on them for the analytes listed in those certificates, the team took the next step.

“We went deep on the 14 samples that we collected that were spread on roads in 2017 and characterized them for far more than what appeared on the certificate of analyses, including the obvious ones with respect to salt, total dissolved solids, sodium chloride, calcium, et cetera,” Dr. Burgos clarifies. “We also looked at other metals such as iron and lead, and radioactive elements such as radium, and organic compounds. So we looked for gas range organics, diesel range organics, that would be expected to be in oil and gas wastewater.”

After conducting a deeper analysis, the team found elevated radium in the OGW—at far higher levels than expected.

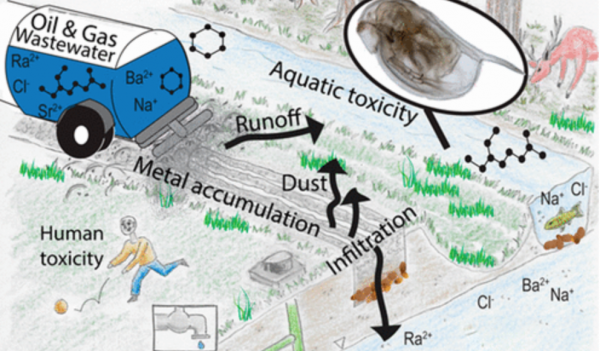

A diagram of how radium in road spreading enters the environment. (Credit: Tasker, et al., https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.est.8b00716)

“Of the 14 samples, I believe the median value was somewhere around 1,200 to 1,300 picocuries of radium per liter—and for perspective, the drinking water standard is 5 picocuries per liter,” remarks Dr. Burgos. “Even the industrial wastewater standard that is sometimes applied to radioactive fluids is 60 picocuries per liter. In this case, we’re talking 1,260 as a median, so some had considerably more than that.”

Radium is a known carcinogen. Exposure to high levels of it increases one’s risk for bone, breast, and liver cancer.

“It’s clearly something you want to have some control over in this situation,” quips Dr. Burgos.

Dr. Burgos and the team also applied OGW brines to road aggregate repeatedly, to simulate what happens when a brine is reapplied to a road over and over again—a common occurrence. Road aggregate exposed in this way reached a plateau level of radium eventually, meaning that sooner or later, road aggregate stops absorbing the radium, and the rest of it runs off the road and leaches into soil or water.

“We completed toxicity testing with respect to human cells and Daphnia Magna, which is a water flea, and as you can expect, these fluids displayed great toxicity both to aquatic organisms and to human cells,” states Dr. Burgos. “There’s no question there’s toxicity associated with these fluids, but the most significant finding was probably that this disposal option of spreading oil and gas wastewater on roads is the single largest source of radium being added to the environment by any of the oil and gas wastewater disposal options.”

In other words, thanks to this surprising (and for most people, unknown) disposal practice, the largest source of radium into to the environment has been coming from road spreading that we were intentionally using.

“We knew as this work went forward that this could be a very volatile story,” adds Dr. Burgos.

For now, the team is hoping their research will help establish OGW “road spreading” standards and treatment guidelines that can help reduce possible environmental damage from this practice.

Top image: A water truck sprays down a dusty road on a construction site. (Credit: By Smurrayinchester [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], from Wikimedia Commons)

Melissa Troutman

September 4, 2018 at 8:01 pm

Dear Ms. Lant,

In Pennsylvania, wastewater from unconventional “fracked” oil and gas wells is not permitted. Only wastewater from conventional oil and gas operations. It is this conventional wastewater that Dr. Burgos studied. Please make note, for your statement above – “fracking wastewater had an officially approved “beneficial” use being sprayed on roads.”

Thank you for your attention to this issue and for an excellent interview with Dr. Burgos.