Tracking Opioids in Municipal Wastewater

Aparna Keshaviah before speaking at the Society for Risk Analysis. (Credit: Aparna Keshaviah)

Aparna Keshaviah before speaking at the Society for Risk Analysis. (Credit: Aparna Keshaviah)By 2016, tens of thousands of Americans were dying with opioids as the primary cause of death. This has prompted officials to search for new ways to intervene, producing a need to monitor and track how and where people become addicted to opioids. However, due to legal risk and social stigma, self-reported opioid use is not always accurate, leaving public health officials hungry for good data. Moreover, the typical data sources used to monitor community drug use have serious time lags that hamper real-time decision-making.

This issue has inspired recent work into tracking opioids in municipal wastewater from researchers at Mathematica, an employee-owned company dedicated to improving public health and wellbeing. Aparna Keshaviah, Sc.M., a senior statistician at Mathematica, spoke to EM about the work.

“In 2016, a group of us started looking at the opioid epidemic,” explains Ms. Keshaviah. “It had been in the news for a long time, and we realized that the traditional ways of tackling the problem weren’t working, from the way we’re asking questions to the data sources that we’re using. We came across this idea for wastewater testing, which had been used to track other illicit drugs like cocaine, and even things like pharmaceutical and personal care products. Yet there hadn’t been a lot of talk about using wastewater testing for opioids.”

But more addicts, patients, and overdose deaths have forced policymakers to look for better, more timely answers, and the team was hoping to provide them with some.

“We started looking for better data sources because through our behavioral health work with SAMHSA [the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services], we saw that traditional drug surveillance data has terrible lags and some serious limitations,” details Ms. Keshaviah. “The most common data sources are national population surveys, which are typically not available until one to two years after the data are collected. We’re always playing catch-up with these surveys, which also lack resolution geographically, and present problems because of biases and underreporting of a stigmatized behavior.”

Adding in the healthcare data from first responders and emergency rooms—known as “consequence data” because it’s frequently collected after an overdose when it’s too late to intervene—reveals biases as well.

The program from A Symposium on the Potential of Wastewater Testing for Public Health and Safety. (Credit: Aparna Keshaviah)

“These data miss people who are outside of the healthcare system, which can really be a substantial portion of people who use illicit drugs,” Ms. Keshaviah describes. “We realized that there is a need for a better, more real-time, and objective data source that isn’t prone to problems because an individual misremembers or misreports their substance use. So we started looking into whether wastewater monitoring could be used to provide a real-time measure of opioid use in a community.”

The need for wastewater monitoring data

Tracking a community’s drug use through wastewater testing, offers rich data that can yield geographically precise measures, usually at the county level.

“Because of the infrastructure put into place as a result of the Clean Water Act in the 1970s, we actually have fairly routine and consistent processes for sampling that are already being used across the country,” states Ms. Keshaviah. “Tapping into that to get data on community drug use started our thinking.”

The team noted a gap in the literature that was probably hampering the work of policymakers.

“Many of the publications we saw were not focused on opioids, and most were also within the academic realm, published in peer-reviewed journals only,” comments Ms. Keshaviah. “Many people on Capitol Hill weren’t even aware of this methodology. We saw the perfect opportunity to bridge the silos that exist in this work.”

This research was shaped not just by questions about opioid use, but also by who has a need for that data.

“Self-reporting is simply not that reliable,” remarks Ms. Keshaviah. “Even if it is consistently under-reported so that you could track trends reliably over time, that doesn’t help the police officer, the first responder, or the front line clinician know what drugs are emerging in the community.” This lack of timely transparency hinders effective prevention and treatment.

The recent Fentanyl scare across the country is a great example of this problem and the need for more granular data.

“We started to hear about highly potent Fentanyl being mixed in with heroine a couple years ago—something that water testing possibly could have picked up if used for surveillance in the way we are recommending,” Ms. Keshaviah says. “It’s hard to detect Fentanyl in a single individual who comes into the E.R. with an overdose because it’s consumed in such small quantities. But when you’re looking collectively at a community it’s much easier to detect whether there is any Fentanyl there, yes or no. Law enforcement agencies then know, for example, that their officers need to be wearing protective masks when they see drugs on the street since coming into contact with even a few grains of Fentanyl can be deadly.”

These kinds of data can also help educate and protect public health and safety.

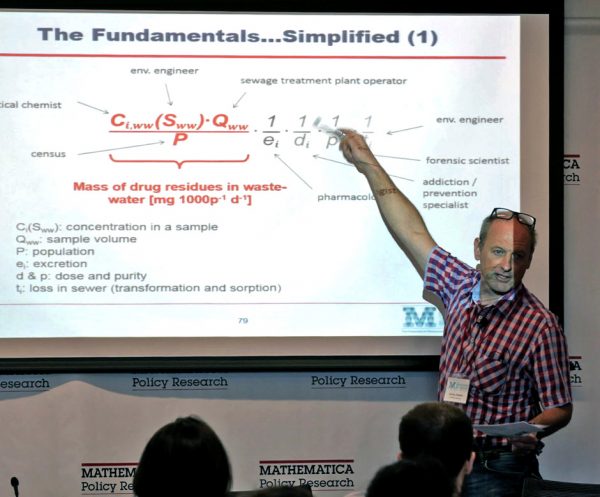

Dr. Jochen Mueller, a colleague from University of Queensland, Australia, speaks at the symposium. (Credit: Aparna Keshaviah)

“People often have no idea what they’re taking,” adds Ms. Keshaviah. “They think they’re buying one drug and they’re actually getting something else. So self-reported data on drug use can be problematic. But the chemical analysis doesn’t lie. It will tell you what people consumed.”

Two methods for monitoring wastewater

There are two different ways to analyze wastewater for compounds like opioids.

“You can do targeted testing for specific compounds, to see how much of a compound there is circulating in a community,” explains Ms. Keshaviah. “You can also do untargeted testing if you don’t know what you’re looking for and want know what all is in the wastewater. You get a chemical profile for a sample and compare it manually against the signatures of known compounds in the universe.”

This is more labor intensive, but important because new pharmaceutical trends arise frequently, and some are dangerous.

“For example, a few years ago, populations starting abusing Imodium A.D., also known as loperamide, to get high cheaply with an over-the-counter drug,” Ms. Keshaviah describes. “That’s something we wouldn’t know to look for as a drug of abuse. And although it’s labor intensive to test for unexpected compounds, you don’t have to do that every day. You can do untargeted testing periodically in an area, to get an early warning as new drug threats emerge.”

Localities or public health agencies can also conduct targeted testing to determine whether to use of problematic compounds is decreasing, increasing, or plateauing in response to policies or programs.

“There are some place-specific challenges because wastewater treatment plant designs vary,” details Ms. Keshaviah. “In some locations, stormwater mixes in with sewage and industrial runoff, which can dilute concentrations of drugs and make them difficult to detect. In other places, it’s more of a closed system. By understanding that kind of variability across the country, you can try to correct for its effects when developing wastewater sampling plans, back-calculating estimates of use, and comparing estimates from one region to another.”

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) generated the foundational idea to use wastewater testing for community drug use in the early 2000s. And although one of the first pilot studies was conducted in the U.S., by ONDCP [the Office of National Drug Control Policy], the methodology never fully caught on in the U.S. and was instead first adopted widely in Europe. Many protocols for sampling have been developed by a network of researchers abroad, and wastewater researchers here in the U.S. are collaborating with their international colleagues and learning from them.

“Wastewater testing is actually being used as a routine surveillance tool around Europe, Australia, and increasingly in China,” comments Ms. Keshaviah. “While it hasn’t been adopted widely in the U.S., we have seen an uptick in the number of pilot studies here in recent years. Mathematica hosted a symposium in 2017, funded by Arnold Ventures, with the goal of raising the profile of the methodology, talking through what kind of information various stakeholders need, and whether wastewater testing could address the challenges they face in their day-to-day work on the opioid epidemic. Data and lack of resources were the top two challenges that everyone mentioned.”

Compared with national surveys, wastewater monitoring is a fairly cost-effective technique.

Aparna Keshaviah discusses tracking opioids in municipal wastewater. (Credit: Aparna Keshaviah)

“The methodology taps into infrastructure that already exists,” Ms. Keshaviah says. “The wastewater plants already collect samples every day. In these pilot studies that we are helping to implement, the wastewater treatment operators are actually donating much of their time and efforts—because they are already doing the work.”

“The opioid epidemic is not going away anytime soon, and there is now funding to help states address the issue,” adds Ms. Keshaviah. “But states need ideas for new approaches. ‘We have tried a lot of things, what else can we look at,’ they ask. There is this kind of plea for better data, more help, and novel strategies to combat the problem.”

Better data for proactive policymaking

More interest in collaboration is fueling a need for wastewater pilot studies, especially as the full potential for the technology is explored.

“We’re developing a list of wastewater researchers in the U.S. so that when we get a cold call from a clinician who wants to start a pilot study, we can connect them to local wastewater researchers,” explains Ms. Keshaviah. “Actually, you can test for many different population health markers with wastewater, including medication use, compliance with Tamiflu prescriptions during flu season, the prevalence of chronic diseases like diabetes, or trends in obesity. Increasingly, researchers are even able to parse out different types of microbiomes, which can really influence your susceptibility to different diseases. And you can track things like viruses and other pathogens, such as polio and hepatitis, to try and predict future outbreaks before they happen.”

Wastewater data is even more powerful when combined with other data sources. Among the reasons wastewater testing hadn’t been used for opioids in the past is the fact that many different opioids convert into the same compound, morphine, over time.

“In studies in Europe, we’ve seen data triangulation successfully used to parse out illicit use from prescription use. Here in the U.S., we could combine wastewater data with prescription drug monitoring program data, and use information on how many prescriptions were written in the area to try to triangulate illicit opioid use,” describes Ms. Keshaviah. “The methodology is even being used to estimate the size of the black market for marijuana after a state has legalized recreational use. You can use wastewater data to estimate total marijuana use, and then subtract out legal use based on marijuana sales data, to get an indication of black market sales.”

Up next for the team working to promote this technology?

“Wastewater testing is such an underutilized data source that we’re still trying to figure out what the real challenges are for adoption,” remarks Ms. Keshaviah. “It’s preliminary, but there is definitely interest from the government. For example, we’ve been briefing FDA, NIH, and other agencies on the methodology since the symposium, and we learned that NIH/NIDA just created a new funding stream for small businesses to improve wastewater testing methods.”

This may well be a moment for this kind of data collection, and the people who can put it to better use.

“There are so many interesting questions that are of policy relevance, comments Ms. Keshaviah. “This work is so very early in the U.S., and this is really where Mathematica is trying to help bring the tool to the people who need it, who can make decisions with it to improve public health and safety. And as a statistician, I’m very happy to lead this charge and make the case that we need better data! People are starting to listen now. There is a lot more receptivity to new ideas and new ways of doing things.”

0 comments