Tsunami’s Effects Lasting Years for Marine Creatures

The Great Pacific garbage patch causes vast quantities of trash to wash ashore at the south end of Hawaii. (Credit: Justin Dolske from Cupertino, USA [CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)])

The Great Pacific garbage patch causes vast quantities of trash to wash ashore at the south end of Hawaii. (Credit: Justin Dolske from Cupertino, USA [CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)])Adrift on the open ocean, even aquatic species can feel stranded, without their usual habitats and food sources. This has been the situation for various species post-2011 Japanese tsunami for years now. Researchers are digging into the lasting effects this displacement could have on them—and on the places they end up. Dr. Linsey Haram, a postdoctoral fellow at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC), spoke to EM about her research following the winding path of some of these species.

“I wasn’t directly involved with the tsunami debris work because I hadn’t started working at the Smithsonian,” explains Dr. Haram. “I started more than a year ago on a related project looking at whether or not coastal species are on marine debris in the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre (gyre), or the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. We’re looking for actual tsunami debris that’s still floating out there, but we’re also looking for coastal organisms in general that have come into the gyre on various kinds of debris from either Asia or North America. There’s a long story to the Japanese tsunami debris.”

A tsunami ends, but once a tsunami carries the debris into the water, it’s an entirely new problem.

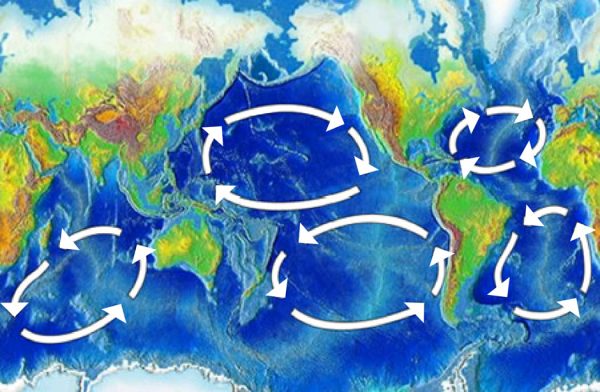

“The currents in the North Pacific encircle the gyre, creating a low flow environment where plastics could get stuck, maybe for decades. This plastic floating out there for a long time may create an entirely new habitat that wasn’t there before,” details Dr. Haram. “It’s a really interesting problem, for sure.”

Studying a new, transient habitat

The gyre is difficult to study, and the team is relying on collaborations to achieve their goals.

“I have yet to go out to the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, actually,” remarks Dr. Haram. “I have recently created a citizen science project, the Floating Ocean Ecosystem Tracker, that will be the main source of our debris collections if it comes to fruition. I believe that will be the best way to do it going forward because it’s really expensive to get out to the middle of the ocean.”

Dr. Linsey Haram. (Credit: Smithsonian, https://serc.si.edu/staff/linsey-haram)

SERC, where Dr. Haram works, and the Smithsonian at large, are uniquely suited for making citizen science work for projects like this.

“There are legal logistics and things like that to work through, but we pride ourselves on a history of successful citizen science projects, and I think there’s a good way forward,” comments Dr. Haram. “And now it is off the ground and running.”

Although many people have heard of the gyre, at least under the moniker “Great Pacific Garbage Patch,” most of what there is to be known about it remains a mystery. Several recent studies have revealed that the gyre is growing as more plastic accumulates there every year.

“The major misconception is that it’s actually a patch or an island. It’s not,” clarifies Dr. Haram. “It’s an area of high plastic accumulation. Much of it is microplastics suspended in the water column, so from the surface, it doesn’t really look like there’s a lot of plastic.”

In reality, though, the accumulation is substantial. Numerous animals have clung to debris and washed up along the California and Pacific Northwest coasts at least since 2012—despite the fact that the 2011 Japanese tsunami was a full 4,300 miles away. And while scientists don’t know if the tsunami debris was in the gyre prior to coming ashore in North America, or if it was circulating on major ocean currents, they hope to determine whether or not tsunami debris and its hitchhikers are present in the gyre right now.

“If you were to get into the water or to run a net through the water column, you would see that there are millions of particles in the water below you,” remarks Dr. Haram. “Researchers have estimated there are trillions of pieces of plastic in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, which is pretty incredible.”

There are five major ocean-wide gyres — the North Atlantic, South Atlantic, North Pacific, South Pacific, and Indian Ocean gyres. Each is flanked by a strong and narrow “western boundary current,” and a weak and broad “eastern boundary current”. (Credit: NOAA, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Oceanic_gyres.png)

Although these coastal species were previously thought to be incapable of surviving open ocean conditions, they are surviving for many years on the open ocean—years longer than ever recorded before. The question is what their survival means for them and the ecosystems in which they eventually land.

“At this point, we don’t really know,” states Dr. Haram. “There have been articles about plastic ingestion by gooseneck barnacles, but beyond that, we don’t really know much, which is unfortunate. Really what we’re focused on at this point is identifying the extent to which coastal species are living in the gyre and whether or not they’re reproducing there.”

The team hopes to someday describe how the species are living and eating in the gyre, but for now, that is beyond the scope of the project.

“We won’t be able to fully answer questions such as how and what they’re eating without laboratory studies, and that is on the horizon,” explains Dr. Haram. “At this point, we’re focusing mostly on describing the coastal species that are there, where they’re coming from, and how they’re interacting with the open-ocean species that are supposed to be there and are already adapted to open ocean life. Those are our big questions at this point.”

Studying a habitat that’s a little too permanent

Research into animal travel on tsunami debris is also ongoing. Specifically, some teams are testing the idea that more species are traveling on the ocean now that there is more plastic in it—often accidentally, whether after extreme weather events or as a result of problems such as entanglement.

“Many of these species that we find out there are organisms that settle on open space somewhere along the coast, and then inadvertently get picked up and pushed out to sea,” Dr. Haram describes. “That goes for some of the fish species, too. It’s accidental hitchhiking, essentially. Then they get pushed out to sea with whatever debris it is that they were with along the coast.”

Japanese tsunami debris on the open ocean, March 2011. (Credit: Alexander Tidd [Public domain], https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Aerial@sendai.jpg)

“Plastics are an amazing material,” remarks Dr. Haram. “The truth is that we don’t actually know how long it takes these sorts of things to break down, because when they’re tested for stability, it’s not in an open ocean environment. It’s a lot harsher out there with UV bearing down and wave motion. There’s a lot of work that needs to be done about the actual life cycle of different types of plastic in the open ocean, I think.”

Meanwhile, with durable new floating habitats come the possibility of invasive marine species—or invasive land species that arrive via the water.

“Invasions tend to be up to chance in many ways,” comments Dr. Haram. “It depends on where you are in the environment, what native species are already in place, and the characteristics of non-native species. Some non-native species could be more predatory than native species, for instance, and then they could disturb the food web by eating prey that other native species were eating previously.”

This is the classic example, but not the only kind. Dr. Haram has studied an invasive seaweed whose invasion was essentially forming an entirely new habitat passively in the Southeastern US.

“In that case, it wasn’t eating things, and things weren’t necessarily eating it,” remarks Dr. Haram. “Some of the heat-reducing properties and its physical structure were making it a great place for many native invertebrates to live. It was pretty incredible, and there’s been a big debate about whether or not it’s actually a positive or a negative introduction, getting into some of the dynamics of invasive species research values and ethics was also really interesting.”

Meanwhile, the project will continue to sample, perhaps with the help of citizens.

“We’re going to try to collect as much debris from the gyre as possible and look for what’s living out there, whether it’s coastal or open ocean species, determine where they came from, and hopefully acquire some insight into the ways that they arrived, either via the tsunami or just everyday trash influx to the gyre,” adds Dr. Haram. “We don’t know a lot about that at this point, which species are going to the gyre just because of the everyday movement of debris.”

0 comments