Underwater Camera Captures First Herring Run in 200 Years

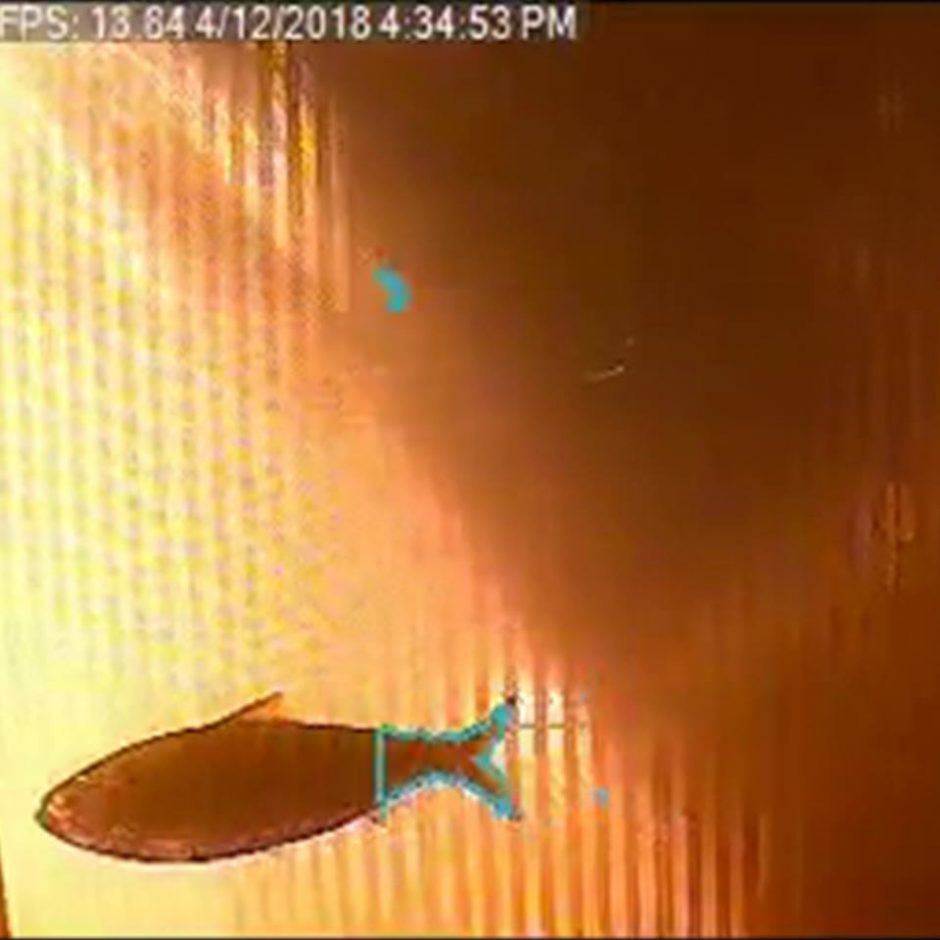

The photo below was taken from the underwater camera at the Lake Sabbatia fish ladder. The photo shows the first river herring to swim the entire Mill River since it was dammed in the early 1800's. (Credit: Taunton Emergency Management Agency, https://www.facebook.com/tauntonema/photos/a.306924176007919.79274.298176006882736/1897851180248536/?type=3&theater)

For the first time in two centuries, herring are heading north in Massachusetts via Mill River. A diadromous species, herring spend the majority of their lives in salt water, venturing into freshwater only once a year. Like salmon, herring swim up river instinctively to spawn, making the upstream journey crucial to the survival of the species.

The Mill River once allowed for a massive herring run every year, but once the area became more settled and the industrial revolution began, the need for power in the area meant dams on the river. In the end, three major dam structures choked the herring out.

Starting in 2006, the State of Massachusetts began a 12-year state project called Mill River Restoration. The initiative was a response to a crisis in 2005, during which one of the dams partially failed, putting thousands in danger. It was left open permanently, and the Department of Transportation installed a new bridge and fish ladder that were in place by 2013. Several other dams, dating back to the mid-1800s, were replaced during the same time period.

Recovery for herring

Now the Massachusetts Department of Fish and Game monitors various points in the watershed for herring and other species. Their monitoring efforts include a point at Morey’s Bridge dam on the Mill River en route to Sabbatia Lake.

Sara Turner is a diadromous fish biologist working for the Massachusetts Department of Fish and Game’s office of the Division of Marine Fisheries (MA DMF). Turner corresponded with EM about her work and how surveilling the fish helps decision-makers in the area.

“The video monitoring will provide us information on how the fish populations respond to restoration, which will help inform future restoration project selection and management,” explains Dr. Turner.

Dr. Turner and the team saw the first photo of a herring making its way upstream at this new location on April 12. The image is serving as proof that the dam’s 2013 fish ladder is working. Since that first image, other herring have been spotted along the same route.

The underwater cameras are part of fixed, part-time installations in the area.

“The camera is installed seasonally, the infrastructure is only in place during the migratory season,” Dr. Turner describes. “The camera is in a fixed location, and the housing it is in herds the fish to the viewing area.”

Each weekday some member of the monitoring team drives to Taunton to download data from the dam’s underwater camera. The scientific team doesn’t just monitor herring, either, and some monitoring activities take them to observation sites at night.

“In addition to monitoring river herring response to the restoration, we are also monitoring American eels and sea lamprey populations,” states Dr. Turner. “Eels are the only species in North America that is born in the ocean and migrates to fresh water to grow and feed before returning to the ocean to spawn. Species with this life history are referred to as ‘catadromous.’”

These junctions near dams with underwater cameras actually do two things at once. They capture images of species using ladders and direct them toward an observation area. The cameras themselves are always on duty.

Atlantic herring. (Credit: State of Massachusetts, https://www.mass.gov/service-details/learn-about-atlantic-herring)

“The camera has motion-detecting software, and records when something passes by the frame of view,” details Dr. Turner. “The video clips are downloaded and reviewed by my seasonal staff.”

Knowing how many fish are migrating to different parts of the river allows the team to monitor how able the species is to access potential habitats.

“[The monitoring] is more about understanding how far into a river the fish can get, because the size of a population depends largely on the amount of the habitat available,” adds Dr. Turner.

After 200 years or so of no herring runs, the return of herring to Mill River is a big deal—one that has broader impacts on the area.

“Based on some early monitoring MA DMF conducted prior to this last dam removal, there was a small population of herring in the river, they were just constrained to the very lowest portion of the river,” remarks Dr. Turner. “River herring and other sea-run fish that require freshwater and marine habitats to complete their life cycle, are important because they transfer nutrients between fresh water and the ocean, linking the two environments.”

The capacity to engage in this kind of monitoring is essential for teams like the one at MA DMF. Without confirmation that a species like this is returning, there is no proof that a ladder (or any other strategy) is effective in a given situation. With better technologies like this, a series of tough policy calls and years of work can both get a little easier.

Top image: The photo below was taken from the underwater camera at the Lake Sabbatia fish ladder. The photo shows the first river herring to swim the entire Mill River since it was dammed in the early 1800’s. (Credit: Taunton Emergency Management Agency, https://www.facebook.com/tauntonema/photos/a.306924176007919.79274.298176006882736/1897851180248536/?type=3&theater)

0 comments