Using Data Buoys to Track Sharks in Cape Cod

Despite the bad rap sharks often get in the media, they are incredibly important to marine ecosystems. Still, sharks residing in coastal, high-traffic areas can pose a risk to public safety—as a result, shark tracking and monitoring projects are often conducted in these waters.

Regardless of the bad press, biologists like Gregory Skomal, a Senior Fisheries Scientist with the MA Division of Marine Fisheries, have always been interested in learning more about shark behavior for the sake of informing conservation efforts.

“I was passionate about sharks as a child. I wanted to be a marine biologist, and pursued it through my education and ended up where I am today,” recalls Skomal.

Starting out in a federal laboratory in Narragansett, Rhode Island, Skomal has been studying sharks and other fish species on the East Coast since his early career. Focusing on shark research in his master’s program, Skomal took a position with the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries after completing his studies.

The position was particularly attractive to him as it offered Skomal the freedom to design his own research. In pursuit of his long-term fascination with sharks, Skomal started the shark research program for the agency.

The tagging vessel, Aleutian Dream, prepares to tag a white shark off Cape Cod. (Credit: Wayne Davis, Atlantic White Shark Conservancy).

Great White Shark Monitoring in Cape Cod

Starting in 1987, Skomal conducted shark research off the coast of Martha’s Vineyard before moving off-island 14 years ago. Now, Skomal is stationed in New Bedford, Massachusetts and studies great white sharks, among other species, in Cape Cod. Data collected by the project helps inform public safety protocols and shark conservation efforts.

“As a fishery scientist, the goal we’re always trying to achieve is producing information that will enhance sustainable fisheries management—I work specifically on sharks, and our ultimate goal is to produce information that will go into establishing conservation-based regulations,” explains Skomal.

He continues, “Most of our research is on natural history and movement ecology—it’s producing information that I think will be helpful, and I find it very fulfilling.”

Sharks typically represent apex predators in the food chain, making them critical components of marine ecosystems, as the loss of these species could result in a loss of equilibrium in the ocean. Beyond the environmental and ethical reasons to monitor sharks, federal and state laws require states to manage their natural resources sustainably.

While these efforts support conservation, real-time tracking of sharks produces alerts to enhance public safety for marine recreational activities.

A 17-foot female white shark is observed by the tagging crew off Cape Cod. (Credit: Wayne Davis, Atlantic White Shark Conservancy).

Tracking Great White Sharks

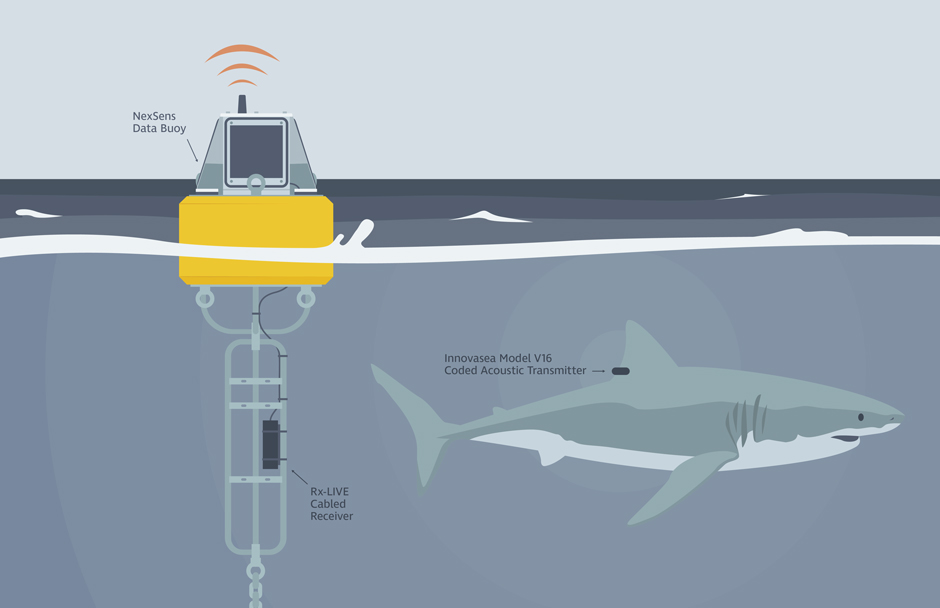

Sharks are tracked by tagging specimens with acoustic transmitters, which are detected by an array of acoustic receivers. These receivers are located throughout Massachusetts’ coastal waters on surface buoys and, in some cases, navigational aids. When tagged sharks swim near one of these receivers, the identification number of that shark is recorded, time-stamped, and stored internally.

Tagging efforts began in 2009, and although great white sharks can be elusive, Cape Cod is one of the few places where the species can be encountered fairly predictably, providing the team with a plethora of data points. In addition to the movement data from the tags, the scientists make every effort to record the sharks on underwater video cameras and collect genetic material for analysis.

He elaborates, “It gives us direct access to this species, really for the first time in history in this part of the world. So, our goals, of course, are to learn about the biology and ecology of this animal.”

“At the same time, because of the presence of this shark in close proximity to some of the most popular swimming beaches in Massachusetts, we’ve suffered from a number of shark attacks, and so we’re also trying to produce information that will enhance public safety,” adds Skomal.

Greg Skomal on the pulpit of the tagging vessel Aleutian Dream. (Credit: Christine Sanders).

Traditional passive acoustic tracking methods can give valuable information on shark behavior, but the need to go out and collect the data from each receiver can slow the flow of information. The receivers are deployed each year around May or June and then retrieved the following January or February.

So, while the data can help researchers better understand sharks, an additional solution had to be developed in order to fulfill the public safety side of the research goals.

In addition to the over 70 standard receivers that archive tracking data, seven NexSens buoys have been deployed for the past several years. These data buoys house Innovasea receivers compatible with the 69 KHz tags placed on the sharks and allow the receivers to conduct real-time monitoring.

In contrast to the internal storage of the standard receivers, NexSens partnered with Innovasea to integrate their acoustic technology with NexSens CB-series buoys, enabling real-time data collection. The receivers document whenever a shark is within the 300 to 500 meter range of the system and then transmit the data to the cloud, which immediately alerts lifeguards on the beach via cellphone that a shark is in the area.

A NexSens data buoy equipped with an InnovaSea receiver that detects when tagged great white sharks are nearby. (Credit: Emma Jones / Fondriest Environmental)

Conclusion

The combination of real-time alerts and long-term data collection allows researchers to study elusive species like sharks in a way that has never been done before—simultaneously balancing data needs with public safety while protecting the species.

The Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries conducts several acoustic tagging projects on a number of marine species. The Innovasea receivers are capable of detecting all of these transmitters regardless of the species tagged.

Skomal elaborates, “We have a network of researchers from Canada to throughout the US that share data. So, I might, for example, pick up a sturgeon that has been tagged by a researcher up in Maine. Those things happen and we get detections from this technology from all kinds of species.”

“Because of my personal fascination with these animals, it’s always very rewarding when I’m able to see them and work with them. And, if we’re able to achieve our goals, then that’s extremely rewarding as well. Learning new things about these animals, having new discoveries about their biology, their ecology, much of which can be very surprising. For me, those aspects are what really drive me,” states Skomal.

His quest to study the biology of this species in the Atlantic is chronicled in his latest book, Chasing Shadows, published by Harper Collins.

A white shark bearing an orange camera tag hunts gray seals along the shoreline of Cape Cod. (Credit: Wayne Davis, Atlantic White Shark Conservancy).

0 comments