Warmer Ocean Temperatures Contribute To Methane Plumes Off Washington Coast

For decades, oceans have been taking a lot of the heat from rising atmospheric temperatures globally. But it looks like all the absorption may finally have caught up with them.

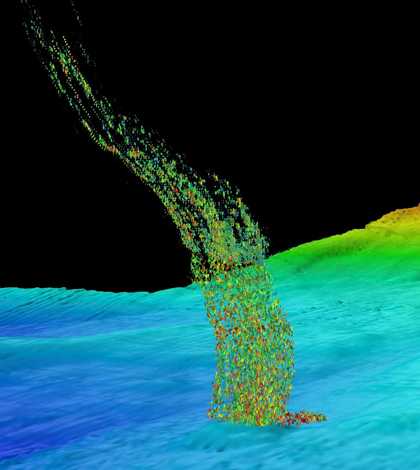

New research led by scientists at the University of Washington has found that warmer ocean temperatures, specifically those measured about a third of a mile below the surface along the Pacific Northwest coast, are contributing to the thawing of methane ice particles. Once they thaw, and change from their methane hydrate form, the particles shift to become gas bubbles that rise to the surface where they add to warming as a greenhouse gas.

The find comes not long after other work done by U. Washington researchers in 2014 that predicted such a shift could occur based on the movement of warmer ocean waters to the area from the western Pacific. The guess was that methane deposits in the Cascadia subduction zone, which runs from northern California to Vancouver Island, would be much less stable with the warmer waters. And it looks like the prediction was right.

“We see an unusually high number of bubble plumes at the depth where methane hydrate would decompose if seawater has warmed,” said H. Paul Johnson, a professor of oceanography at the university and lead author of a study into the issue, in a statement. “So it is not likely to be just emitted from the sediments; this appears to be coming from the decomposition of methane that has been frozen for thousands of years.”

Evidence of the methane releases was first reported by fishermen in the area who could see the rising bubbles on their sonar devices. Forty-five plumes were discovered by fishing boats, scientists say. But they also made cruises with a research vessel to find others, locating a total of 168 plumes of methane up and down the Cascadia subduction zone.

Map showing locations of the 168 bubble plumes used in the study. (Credit: University of Washington)

Only included in the analysis were plumes that rose at least 150 meters (490 feet) and clearly originated from the seafloor. Scientists involved with the effort say that 14 of the plumes are occurring at transition depths, or the depths they have pinpointed as warming. That’s a higher coverage area for the plumes than in surrounding areas off the seafloors of Oregon and Washington.

“What we’re seeing is possible confirmation of what we predicted from the water temperatures: Methane hydrate appears to be decomposing and releasing a lot of gas,” said Johnson, in the statement. “If you look systematically, the location on the margin where you’re getting the largest number of methane plumes per square meter, it is right at that critical depth of 500 meters.”

Researchers note that most of the methane, though not all, appears to be taken up and used by marine microbes on the way to the surface. That doesn’t mean its effects are nullified, as the microbes using the methane convert it to carbon dioxide which contributes to more acidic ocean water.

Scientists are also concerned that the methane plumes could destabilize seafloor slopes where frozen methane acts as the glue that holds steep sediment slopes in place.

“Current environmental changes in Washington and Oregon are already impacting local biology and fisheries, and these changes would be amplified by the further release of methane,” said Johnson, in the release.

Full results of the study are published in the scientific journal Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems. The research was funded by the National Science Foundation and the U.S. Department of Energy.

Top image: Sonar image of bubbles rising from the seafloor off the Washington coast. The base of the column is one-third of a mile (515 meters) deep and the top of the plume is at one-tenth of a mile (180 meters) depth. (Credit: Brendan Philip / UW)

0 comments