Water Quality Program Changing Lives One Student at a Time

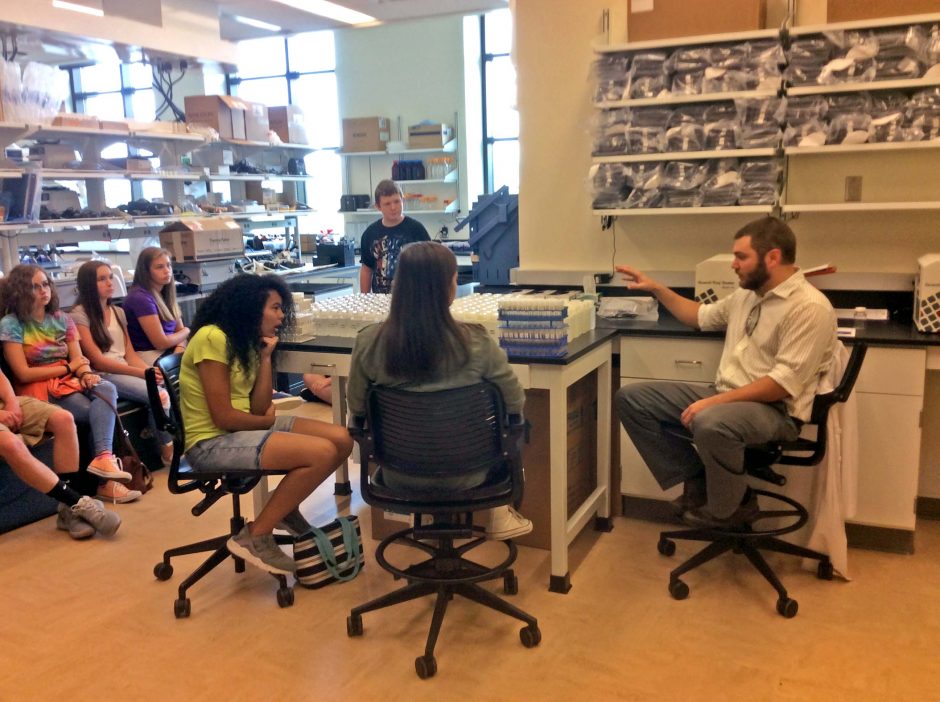

Learning how to use equipment at the lab. (Credit: VT, VHWQP, via source)

Millions of Americans rely on well water at home, and in Virginia well water supplies about 20 percent of households. The Virginia Household Water Quality Program, run by Program Coordinator Erin Ling at Virginia Tech, is offering well testing across the state, helping the people who use that well water understand how to keep it safe and healthy. EM spoke to Ling and Carroll County High School STEM-Ag Lab Manager Rachelle Rasco about the program.

“Our audience was traditionally mostly adults and homeowners, so the ability to reach families that are busy with young children more effectively is always in the back of my mind,” explains Ling. “I met Rachelle because she was participating in a research program for teachers through Virginia Tech, and we started talking about how we could adapt the model that we use regularly for well testing to work with high school students.”

Students get permission from their parents to collect water samples and have them analyzed, and then they physically collect the samples the morning that they’re coming to campus. Most live about an hour away in very rural areas, so they collect their samples and then listen to presentations and visit the lab and talk to scientists at VT—a kind of epicenter for water quality work. This program offers citizen scientists not just an educational opportunity, but also access to important data.

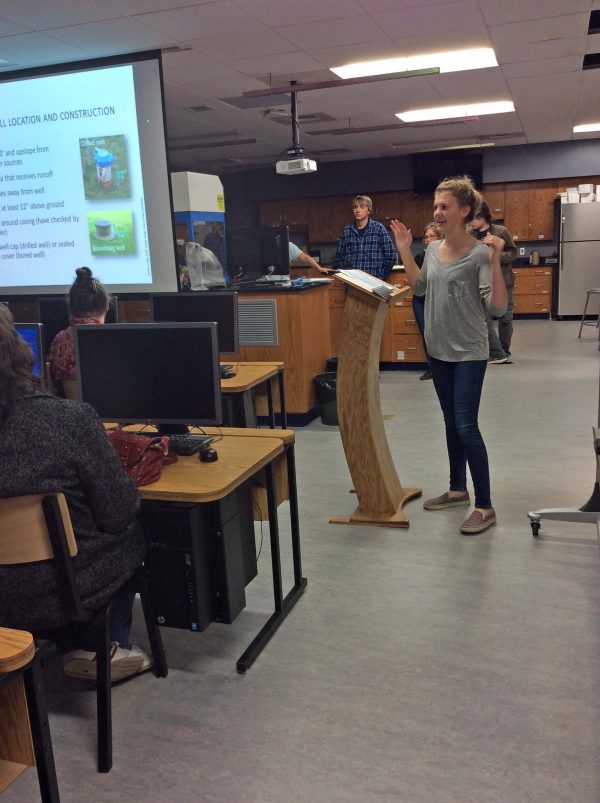

Erin Ling addresses students. (Credit: VT, VHWQP, via source)

“When you can use data to better understand and characterize a problem and a solution, it’s empowering,” comments Ling. “And they can learn from the process, which is why I think this program working with Rachelle is really exciting. The students are learning a lot about what they probably perceive as dry concepts, like pH and calibrating instruments. With this program, we can connect that to understanding the quality and safety of their own drinking water.”

Students in the program receive actual training on both sampling and analysis.

“Usually they’re the ones collecting the sample, or their parent or guardian helps them,” details Ling. “We have a couple of stations set up in the lab, so they’ll learn about a few of the instruments that we use and our method for analyzing for bacteria.”

The analysis includes coliform and E. coli bacteria, nitrate and fluoride.

“We also check pH and conductivity, which we turn into total dissolved solids, and then all of the samples that come through our lab are prepared for all of the other elemental and metals analysis, any contaminants from hardness to lead, copper, iron, manganese, things that geologically get into the water,” Ling describes. “We also have a component of our program to help students better understand what’s happening with lead, copper, nickel, zinc, and other contaminants that are coming from the plumbing components in the home. We can illustrate water chemistry and quality basics, and how they tie into human health and safety to paint a holistic picture of where the water has been, and how it gets changed as it moves through the ground, and then into a well and plumbing. So the students kind of get exposed to all of that, and understand what it takes to put all those pieces together, and how to use different pieces of equipment in the lab.”

Students learn the ins and outs of wells. (Credit: VT, VHWQP, via source)

Students also meet the lab manager, who is an analytical chemist, and study a tabletop groundwater model which shows how water moves underground and how that affects water quality. Furthermore, since Rasco is the manager of the STEM agriculture lab at Carroll County High School, the team ties the VT program to food safety.

“We talk about actually applying concepts of the microbiological safety of water to how our food, specifically produce, is produced and handled,” comments Ling. “And then we have the well drillers come, and there’s some interaction there where they can ask questions, about not only well construction, but about that as a career.”

Well water in Virginia

According to Ling and Rasco, in Virginia, around 21 percent of the population uses well water.

“That water is unregulated, and just for reference, about 40 percent of those samples that we see contain coliform bacteria,” remarks Ling. “About 10 percent contain E. coli, which is a sign that human or animal waste is entering the water supply, and about 16 percent are high in lead. That’s because there are parts of Virginia that tend to have corrosive water, and so the lead throughout the plumbing components gets into the water. So there are pretty significant health and nuisance contaminants across the state.”

The simple truth is, that if you are using well water in Virginia or any other state, you’re on your own, in many ways.

Access to experts at VT. (Credit: VT, VHWQP, via source)

“In Virginia, there are regulations that determine how a well can be constructed and where it can be located, but other than that, it’s completely the responsibility of the homeowner,” says Ling. “Our program offers testing in about 65 counties every year, which is great. But it’s voluntary, and we know from our data that we tend to reach people who are wealthier and better educated than the rest of the population who we know are on wells. So there are a lot of people who don’t test, either because the $55 that we charge for testing is a lot for them, or more because they don’t want to open another can of worms—because if they find something’s wrong, that idea of what you’re going to do about it is really a challenge.”

This isn’t to say the news is all bad for well water users. Well water is a significant component of life in many regions, including Virginia.

“Some people really appreciate having a private well,” adds Ling. “They like having control over their own water, but that comes with responsibility, taking responsibility for testing regularly and treating as needed. And there’s a lot that you can control on your own property, but if wells are located close together or there are concerning land uses nearby, that’s not going to happen, the water can be contaminated.”

This is exactly where the program fits in: on the ground floor, in schools, with students.

“One of the reasons why I really love this program is because a lot of students really don’t understand where the water comes from,” remarks Rachelle. “They have this idea that when they put things down the drain, they magically disappear. They really don’t make the connection with the complete cycle, where water is coming from and where it’s going.”

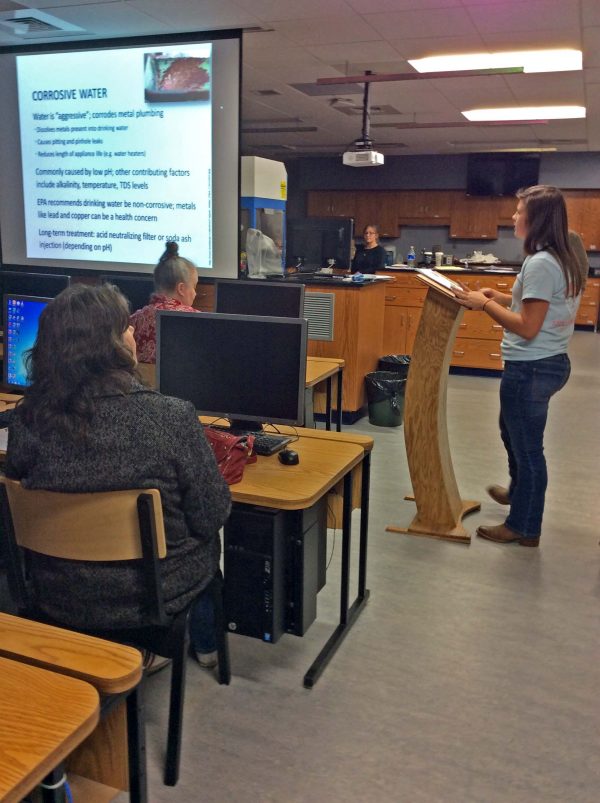

A student presents water quality findings. (Credit: VT, VHWQP, via source)

Program participation is also an anchoring experience for some of the kids who end up going on to do something related.

“We are seeing that, and our student Izzy is an example,” details Rasco. “She is very excited about water quality and global water quality, and this is what she wants to pursue for her career, so she’ll to be going to Virginia Tech this year in the water degree program, and it really all started here with the well water project. A lot of students here are getting experience and seeing some actual jobs that you do with that experience. That’s what’s so great about this program: it’s an application, and it’s personal to them.”

The program also provides a crucial link between academic and practical knowledge for students, with real applications and consequences.

“We’ve also cultivated a strong relationship with the well drillers in the state, the folks who actually drill and take care of the wells,” states Ling. “We’ve tried to build that piece in, for students who are not interested in becoming scientists, but who may have an interest in a vocational career.”

“Yes, it has really tapped into both students on more of an academic track, and those that are looking for more vocational training,” Rasco confirms. “Often in science kids decide they want to be a veterinarian or doctor because that’s really the only scientist they ever have contact with. But having this experience, they see different applications and a lot of overlap in between the two.”

The team together. (Credit: VT, VHWQP, via source)

Thanks to groups like the Virginia Lakes and Watersheds Association, the program is helping more and more households understand what’s in their water—and showing students that they have what it takes to handle problems that might arise.

“I would say 98 percent of the students really enjoy the experience and come back and tell me about it, want to get involved,” muses Rasco. I’ve had quite a few students go on into a research field after this was their first experience being in an actual science lab. The students are busy with sports and jobs and things like that, but usually each year I can convince a handful of them to come back and present the results to the parents, and those that present really feel confident about what they’re doing, and they really increase their knowledge. Sometimes we forget those soft skills, but to be able to communicate this scientific knowledge to a group of adults is really powerful.”

Top image: Learning how to use equipment at the lab. (Credit: VT, VHWQP, via source)

0 comments