Weather Bike Dissects Urban Heat Island Effect

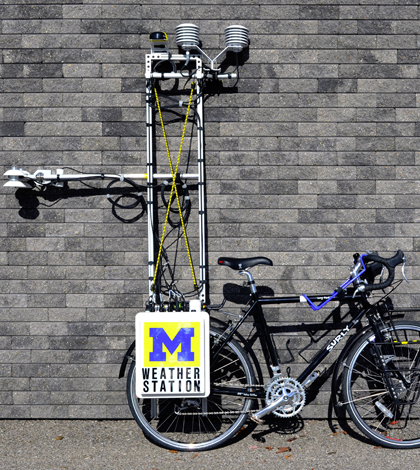

The bicycle-mounted weather station built by Nick Rajkovich. (Credit: Nick Rajkovich / University at Buffalo)

A number of studies have identified higher rates of heat-related illness or death in Cleveland. Those are in many ways thanks to the urban heat island effect created by the city’s neighborhoods that lack trees and the extent that substances like concrete and asphalt cover the city’s landscape.

But Cleveland is not special because its residents are affected by the urban heat island effect. There are many other cities through the United States that grapple with the same problem.

Still more commonality comes through the fact that the issue, regardless of the city you’re looking at, has gone largely unheralded in the realm of climate research when compared to other scientific questions. That’s not to say that the urban heat island effect has gone understudied entirely.

“I think it’s been underappreciated. If you look at temperature changes due to climate change, we expect about 1 to 3 degrees warmer than we have now for the air temperatures found in cities,” said Nick Rajkovich, assistant professor in the Department of Architecture at the University at Buffalo. “With low-income populations living in areas with fewer trees and more asphalt, we’re only just now beginning to appreciate the importance it has. Science is catching up.”

Some of his work is to thank for that. While a doctoral candidate at the University of Michigan, he built a sensor-equipped bike to better measure the impacts of the urban heat island effect. The idea, he says, came from a desire to fill the gaps left by typical methods measuring the effect in cities.

These include systems that are installed on cars or on buildings. Some are even built on push carts. But the problem with some of those approaches is that you can’t collect measurements in smaller spaces, and there is a risk that car-mounted sensors could be influenced by the exhausts of surrounding automobiles.

The first design that he came up with was based on a tricycle platform. This version carried a 3-meter tall tower full of sensors to take weather measurements and was ridden around the streets of Chicago. But Rajkovich soon found that the ergonomics of the trike didn’t do so well over long rides. The second version, based on a cargo bike, was built for a more comfortable experience for the cyclist and continuous data collection.

In the summer of 2012, Rajkovich took the new and improved weather bike to Cuyahoga County, which holds the city of Cleveland, and made multiple long rides through the system of metroparks there. Along the way, sensors on the bike gathered data important for gauging the area’s urban heat island effect.

“I rode around two locations primarily that go from urban to rural,” said Rajkovich. “Which is perfect for understanding how temperature change is built into the natural environment.”

The bike has sensors for measuring temperature and humidity and a GPS for measuring latitude and longitude, as well as the speed of the bicycle. There is also a shortwave and longwave radiation sensor that tracks sky temperatures, solar radiation, reflected radiation and radiation coming off the ground. It also boasts a ground-surface temperature monitor, a barometer and a camera that takes skyview images.

“If you think about how things heat up and cool down, it’s important how much sky an area sees,” said Rajkovich. “The skyview factor measures how open any spot is.”

The whole contraption is powered by an onboard battery pack, though Rajkovich says that not a lot of power is needed because the Campbell Scientific weather station he uses doesn’t draw that much. It can go eight to 10 hours with a limited supply of power.

All of that gear, mounted toward the bike’s rear, makes it a little back-heavy, something that really only impacts the ride when you’re going uphill. But the rest of the time, in touring situations, there’s no such issue as the sensors gather data.

For the effort in Cleveland, Rajkovich says that there weren’t too many surprising finds. In a lot of places, like those near water or trees, he found that temperatures were lower as expected.

“We found some things that we knew were going to happen,” said Rajkovich. “But we think that things like industry and cars have big effects and that’s something that’s not as quantified. We’re interested in learning what happens with lots of highways and industry in places like Cleveland.”

One of those places could include Buffalo, New York, where Rajkovich is thinking about taking the weather bike out next. The differences he might find, he says, could be based on differing weather patterns in the city compared to Cleveland. Buffalo is located on a different part of Lake Erie and sustains much different winds, which can impact its urban heat island effect in varying ways.

“We’ve been talking about riding it around Buffalo. We’re also working on a climate change project with the City of Cleveland,” said Rajkovich. “We want to use it to gather more data, but we only have one bike so it’s hard to take it from location to location.”

The upcoming projects in part mean that there is more and more attention on the importance of studying the urban heat island effect, he says.

“There has been some interest in the urban heat island effect in Great Lakes cities. New York, Atlanta, have had a lot of work done,” said Rajkovich. “People are realizing that this is happening everywhere and that we need more data from other location types.”

Top image: The bicycle-mounted weather station built by Nick Rajkovich. (Credit: Nick Rajkovich / University at Buffalo)

0 comments