Working With Natural Processes—and Beavers—to Improve Water Quality

A female beaver in Devon. (Credit: Michael Symes/Devon Wildlife Trust, https://www.eurekalert.org/multimedia/pub/170038.php?from=393482)

Nature’s industrious architect, the beaver, may help remove excess nutrients from rivers and prevent agricultural soil from losing those valuable nutrients in the first place, according to recent research. A team from the University of Exeter demonstrated the significant impact beavers have on water quality using a captive beaver trial run housing a single family of beavers.

Busy beavers in Devon

The Exeter team, led by hydrologist and professor Richard Brazier, began working with the beavers in 2011.

“For some years I had been researching the negative impacts of soil erosion, flooding, diffuse pollution,” remarks Professor Brazier. “What the beavers do when they build dams seemed like it would make a positive difference to these problems, so the inspiration really came from trying to see if these animals could help with the problems that we have caused.”

Managed by the Devon Wildlife Trust, the enclosure lies within a fenced site along the River Wolf. The captive beaver trial run’s secret location is in West Devon, in the UK.

“Simply put, a captive beaver trial run is an outdoor experiment where we fence the animals into a large enclosure,” explains Professor Brazier. “The mid-Devon trial is 7 hectares, and we let them do their thing, but we also monitor how the whole ecosystem changes. We monitor before and after they build dams, and then also compare results to control sites where there are no beaver dams. We, therefore, quantify the change that the dams bring about. Are flood flows slower with less flow at peak discharge? Is water quality cleaner leaving the site when entering?”

The team is monitoring three fenced-in trials: the mid-Devon trial from the paper, as well as a Cornwall beaver trial and a Forest of Dean trial. There are also three wild populations the team is studying: one on the River Otter in Devon, one in Tayside, and one in Knapdale, Scotland.

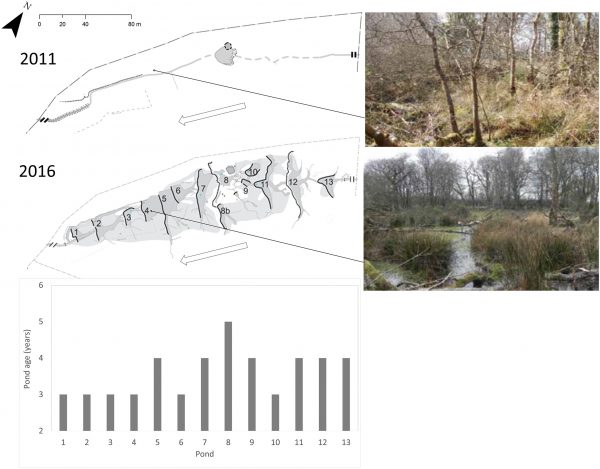

During the seven years, the team has monitored the beavers and the nearby water quality, the family of busy builders has constructed 13 dams, in turn creating many deep ponds and slower flow in the river. This process has also removed high levels of nitrogen, phosphorus, and sediment from the river.

Measuring the impact of beavers on water quality

One of the difficulties of this kind of research is assessing a research site that is continuously changing. The activity of the beavers, along with things like rainfall cause ongoing incremental differences that require close monitoring. Annual surveys covered long‐term monitoring of structural changes, while the team achieved a more detailed “snapshot” of the structure of the site using a survey while sampling sediment.

The team surveyed pond extents using a differential global positioning system (DGPS). They sampled with a ranging pole at every node of a 2-by-2 grid to calculate water volumes and sediment within each pond. Specifically, when the tip of the pole reached sediment, the team recorded water depth; when they pushed through until hitting a compact layer, they recorded the depth of the of sediment. The 2-meter grid layout allowed the team to collect from at least 12 points on each pond.

Schematic showing change in site structure between 2011 (immediately prior to beaver introduction) and 2016. (Credit: Puttock, et al., https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/esp.4398.)

The researchers also took sediment core samples at three randomly selected points for all 13 ponds using a beeker corer. The team analyzed these cores and calculated their weight and density.

The team determined how much nutrients the damming process removed from the water by measuring how much nitrogen, phosphorus, and sediment is suspended in water entering the beavers’ domain, and then comparing the levels to those in the water in the ponds, and the levels in the water leaving the site. The modest dams trapped more than 100 tons of sediment, 70 percent of which was agricultural soil which had eroded from upstream fields. The team’s analysis indicates that the sediment is high in both nitrogen and phosphorus.

In other words, the beavers had a tremendous protective effect on the water quality. The researchers found conclusively that the beavers can help reduce the problem of algal blooms by reducing nutrients: “Absolutely, as they reduce the nutrient loading into the downstream waters, which, in turn, means that there is less nutrient availability for algal growth,” adds Professor Brazier.

Natural dams dotting the landscape

The river the captive beaver trial run surrounds is part of the beavers’ natural habitat.

“It is the River Wolf, so it was probably home to other large mammals in the past as well!” remarks Professor Brazier. “The beaver would have inhabited pretty well all rivers in Great Britain until 600 years ago.”

The team is monitoring the wild beavers on the River Otter in very similar ways, and thus far, Professor Brazier reports that they are delivering similar outcomes.

For the researchers, more comparisons in different locations will come next, along with new ways of testing the idea that beaver dams can help mitigate agricultural soil loss and trap pollutants which lead to poor water quality.

“We’ll be working on more beaver reintroduction across different habitats in Great Britain, which we will then monitor to evaluate whether they provide similar multiple benefits to those we have seen from the mid-Devon trial,” states Professor Brazier.

Brazier and the team are confident that more beaver dams dotting the natural landscapes around the world would mean multiple benefits for various ecosystems. This kind of restoration of ecosystems and protection of water quality is more than just intuitive and efficient: “It is the very definition of working with natural processes,” adds Professor Brazier.

Top image: A female beaver in Devon. (Credit: Michael Symes/Devon Wildlife Trust, https://www.eurekalert.org/multimedia/pub/170038.php?from=393482)

0 comments